The correct veterinary term for Cushing’s disease in horses is Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID). This describes the region of the pituitary gland — the pars intermedia — which is specifically affected.

If you own a horse older than 10, it’s important to be aware of the signs of Cushing’s disease in horses so that you can recognise it quickly and seek prompt help from your vet. Regular reassessments are also recommended, because some of the signs of the disease are commonly mistaken for normal signs of ageing.

What is Cushing’s disease in horses?

Equine Cushing’s disease is one of the most common disease syndromes to affect horse health, according to the National Equine Health Survey in 2018*. It is estimated that 20% of horses and ponies over the age of 15 are affected.

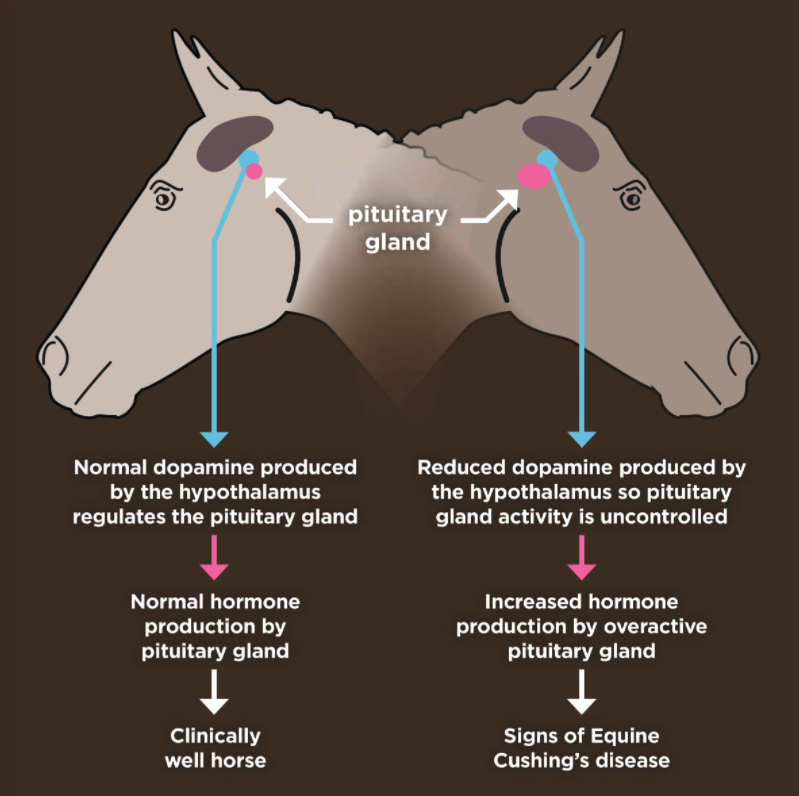

In order to understand what occurs in a horse with Cushing’s, it helps to be aware of what happens in a normal horse without the disease.

Normally the hypothalamus, a small region of the brain, produces a substance called dopamine which regulates hormone production by the pituitary gland. This is located at the base of the horse’s brain.

The pituitary gland produces a variety of hormones that play an important role in maintaining and controlling many bodily functions.

However, horses and ponies with Cushing’s disease don’t produce enough dopamine, which means that the pituitary gland becomes uncontrolled and produces too many hormones.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is one hormone that is produced in excess, although it is likely that there are also many others.

Signs of Cushing’s disease

There are a multitude of clinical signs associated with Cushing’s disease in horses, and the combination of signs will vary from one horse or pony to another.

It’s important to be aware of all of the clinical signs of the disease as early ones are often overlooked, or can be mistaken for normal signs of ageing, which can delay diagnosis and treatment. Other signs may develop over time as the disease progresses.

Laminitis

The signs of laminitis can vary from mild changes in the hooves through to severe lameness. Horses with Cushing’s disease are at an increased risk of developing laminitis compared to older horses without the disease.

Muscle wastage

This is usually seen as a loss of topline over the affected horse’s back.

Abnormal fat deposits

Fat can develop in abnormal places. This is usually seen as a pot belly and ‘fat pads’ over and/or around the eyes.

Abnormal sweating

Patchy or abnormal sweating patterns, or unusually high levels of sweating after low levels of exercise in cool temperatures, may occur.

Recurrent infections

Horses with Cushing’s disease are more susceptible to infection. These may be seen as signs of infection that don’t respond to treatment as expected, such as an infection that keeps coming back, or a high worm burden.

Lethargy

Typical signs of lethargy may be that your horse appears less interested in exercise or their surroundings, or they may not be interacting with you as they normally would. Lethargy can sometimes be difficult to spot as the onset is often gradual and may sometimes be mistaken for a horse getting older. Learn more about this illness here.

Increased thirst and urination

This is not always easy to spot. It may be seen as a sudden change in the amount of bedding that is required to keep the stable dry, or a change in how frequently you need to fill the horse’s water trough/bucket.

Abnormal hair coat

Early disease is frequently associated with delayed moulting and patches of long hair which appears to be curly. Advanced disease usually causes a more generalised hair coat and complete loss of the seasonal moulting pattern.

Reduced fertility

Mares with Cushing’s disease may have diminished fertility, and so their ability to get in foal may be reduced.

Diagnosis and treatment

The ACTH test is the simplest and most common test for Cushing’s disease in horses.

A vet will take a blood sample and send it to a laboratory to measure the levels of the hormone ACTH. High levels will indicate that your horse has Cushing’s disease.

Once a horse has been diagnosed, there are many management strategies that can be implemented to ensure that they remain happy and healthy. These are:

1 Medical treatment

If appropriate, your vet may prescribe lifelong medication to treat the clinical signs associated with Cushing’s disease, for example a daily dose of the tablet Pergolide.

2 Nutrition

Correct nutritional support can help a horse or pony cope better with the consequences of Cushing’s disease, such as muscle wastage. In most cases lifelong medication is needed to alleviate the symptoms. Some horses may also show clinical signs, such as weight loss, obesity, or a predisposition to laminitis, which means they will require an individual nutrition plan.

3 Preventative care

In addition to equine Cushing’s disease, there are a wide range of common diseases that horses and ponies are at risk of developing as they get older, such as dental and musculoskeletal disorders. Preventative healthcare is important for all older horses, but especially for those with Cushing’s disease, so always ensure you pay special attention to hoof care, dental care, vaccination, wormer administration and nutrition.

4 Exercise

Many horses with equine Cushing’s disease are able to continue their athletic careers, and exercise is always helpful for their metabolism. If your horse is sound, then keep up their regular exercise. For those who are less athletic but sound then you could try to ride, long-rein, lunge or lead them out at a brisk walk regularly. If you are unsure whether it is suitable to exercise your horse then seek advice from your vet.

What to do next

Finding out that your horse has equine Cushing’s disease can be worrying, which is why ‘Care About Cushing’s’ was created. If you suspect that your horse or pony is showing signs of Cushing’s disease in horses, book a visit from your vet.

They will examine your horse and, if appropriate, carry out a test to check for the presence of PPID. They may be able to claim a complementary diagnostic test on your behalf through Care About Cushing’s.

*View the full 2018 National Equine Health Survey findings here.

Lead image © Royal Veterinary College. Diagram © Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media Ltd