Basic tack must-haves when you are planning to ride a horse are a saddle and bridle. There are different styles to consider and you’ll need to know how to fit them both properly. This tack also requires certain accessories — such as reins for the bridle and a girth for your saddle — as well as somewhere secure, spacious, well-lit and ventilated to store it.

Horse riding is an incredibly exciting and healthy pastime, albeit an expensive one. By investing in the correct pieces of tack and looking after them well, you will be best placed to enjoy lots of special moments with your horse.

There are other optional items of gear you may choose to have too, but everyone needs to start somewhere and this is what this article will help with.

To help you kit your horse out properly, here is a summary of all the tack you will need:

Saddle

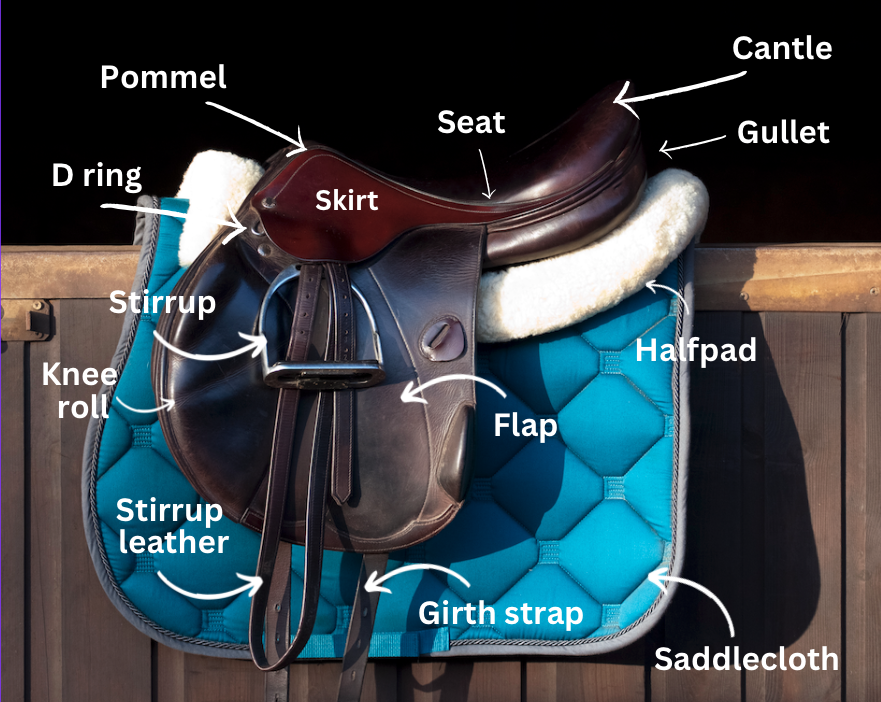

The saddle sits on your horse’s back and is held in place with a girth.

- The front of a saddle is called a pommel, which is shaped to allow room for the horse’s withers to fit underneath (as a guide, you should be able to fit two or three of your fingers in the gap).

- The back of the saddle is called the cantle.

- The area between the two, where you sit, is the seat.

- Between the pommel and the cantle is the gullet. This is the ‘tunnel’ you can see when you stand immediately behind a horse (which isn’t the most sensible of places to be standing, so be careful).

If you can see daylight all the way through, it means the saddle is not sitting too low and pressing on the horse’s spine. - Inside a saddle is the ‘tree‘ (unless you buy a treeless saddle).

This is what gives the saddle its shape and fit. If a saddle is dropped or damaged in any way, the tree must be checked by a professional to make sure it is still in tact and in good working order. - Most saddles also have D rings on either side of the pommel, which a breastplate can attach to.

- The saddle flaps are the two large areas on either side that are underneath your legs. Some saddle designs don’t have a flap so that you feel closer to the horse.

- You’ll find the girth straps beneath the saddle flaps (or just below on some styles).

Buying a saddle

There are several different styles of saddle, each designed for a particular discipline. The most popular designs are for dressage, jumping, showing and general purpose (GP) riding. There are also saddles for racing and side-saddle, as well as basket saddles for young children.

A stock saddle is used for working cattle. I rode in one of these for hours at a time every day when working in Australia as a jillaroo, mustering cattle. They are very comfortable and have big knee blocks either side of your thigh to help keep you secure when whizzing about at fast speeds.

A Western saddle with a horn at the front (possibly with a lasso hanging off it) is a common sight in disciplines like barrel racing, reining and rodeo, all of which are popular in the USA.

Buying a saddle isn’t easy. The choice of saddles for horse and ponies is huge, the price tags are hefty and there’s a lot to consider in order to find the best one for you and your horse. The most important thing to consider about your saddle is that it fits you and your horse correctly.

A poorly balanced saddle can shift or sway, lacking the balance necessary for you to maintain an effective position, which in turn will affect the way your horse moves.

A well-fitting saddle should distribute pressure equally across your horse’s back. It will also help you maintain the correct shoulder-hip-heel line, with your weight carried evenly through both seat bones.

Further reading:

- Diana Fisher, a Society of Master Saddlers registered saddle fitter, explains how to correctly fit a saddle in this video

- Searching for a new saddle? This buying guide will help you make an informed decision

Stirrups

So you’ve got a saddle to sit on, now you’ll need somewhere for your feet. This is the job of the stirrups, which attach to the stirrup bar that you’ll find under the skirt (a small flap) on both sides of the pommel via stirrup leathers.

Once upon a time, stirrup irons were all made of stainless steel and the only choice you had to make was whether to have black or white treads at the bottom to give your boots better grip (I like black because they’re easier to keep clean).

A child could have Peacock stirrups, a safety design with a rubber band on the outside that would flick off to release the foot in the event of a fall.

Oh how times have changed! Now there are stirrups made from plastic and other such materials. Some are so lightweight that you barely know they are there.

Styles with bent bars for increased comfort and security (I use Sprenger Bow Balance Safety Stirrups because they’re kind on my knees); others with no outside bar at all for safety; some with a quick-release mechanism to free your foot if you fall off.

Stirrups come in vast colours too. German event rider Michael Jung famously goes cross-country in a lightweight safety stirrup that is red and black. They are made by Freejump and are more triangle shaped than the conventional closed ‘n’ shape.

Stirrup leathers

Budget stirrups start from around £25 (US$31) and go up to hundreds of pounds and dollars. Shop around before you buy and make sure you know what’s most important to you. Key features to look for and consider include:

- How much does each stirrup weigh?

- What style and shape do you like?

- What safety features do they offer?

- Are there choices in colour?

- How much do they cost to buy?

When you’ve made your selection, you’ll need to buy a pair of stirrup leathers so that you can attach the stirrups to your saddle.

Most saddle manufacturers also make stirrup leathers that can you buy at extra cost so that they match and fit your saddle well. If your saddle is brown, for example, you’ll want brown stirrup leathers rather than black.

I use Wintec leathers on my Wintec GP leather-look saddle, for example. My sister prefers true leather and she has Kent & Masters stirrup leathers to use on her Kent & Masters saddle.

Different riders like different things. It’s just a case of finding what you like and what suits you and your horse best.

You may think of your stirrups as merely something to rest your feet on and give you a bit more security in the saddle, but they are so much more than this.

A good pair of stirrups is a key piece of every horse rider’s tack, and the right set can make a world of difference to your riding position, comfort, effectiveness of your leg aids and your safety.

- Looking for new stirrups? Check out our selection

Bridles

A bridle goes on your horse’s head and can be used for riding, lunging and leading. As with saddles, correct fit of a bridle is vital and there are numerous designs to choose from.

The reins are considered a part of the bridle (but are sometimes sold separately), and the reins are the connection between your hands and the horse’s mouth.

Unless you choose a bitless bridle (sometimes called a Hackamore), the bit you choose — this is the part that goes in your horse’s mouth — will be a part of the bridle too, although they are bought separately.

The bridle you use is a key line of communication between you and your horse, and ensuring it fits well and your horse is comfortable is crucial. Buying an off-the-peg bridle is the option for most and this brings some potential limitations on fit, as all horses are unique in their head shape — and many aren’t symmetrical.

Further reading:

Bridle styles

Traditionally, bridles are made of leather, but there are increasingly large numbers of synthetic nylon and leather-look styles available, which can be cheaper and easier to care for. It’s always worth bearing in mind when buying a new bridle that synthetic tack has a much higher breaking point than leather.

Another consideration is the shape and type of head your horse has. A chunky, cob-type horse tends to have a large, broad head, which is best suited to a bridle with wide straps and noseband.

Conversely, a fine Arab or show horse’s head will look better in a more delicate bridle with thinner, more detailed leather. The anatomy of your horse’s head is a very important factor in bridle fit.

Bitless bridles

A bitless bridle removes pressure from your horse’s mouth and, depending on the type of bridle you use, will place pressure on different parts of the head.

There are lots of reasons why you may choose to ride your horse in a bitless bridle: perhaps they have a mouth injury which means wearing a bit is painful, or they are extremely sensitive in the mouth.

For many owners they believe, from a welfare point of view, that removing the need for a bit is quite simply a kinder way to ride. However, going bitless isn’t for every horse and it’s important to remember that it’s not a replacement for good riding and training.

Leather-look bridles

There was a time when leather was the only material all tack was made from, but webbing headcollars are now considered normal and it wasn’t too long before synthetic bridles appeared on the market.

Some traditionalists won’t entertain using a synthetic bridle on their horses, but there’s definitely a place for them whether they’re made from webbing or a leather-look material.

I have used a synthetic bridle before. It was bright blue (one of my poor teenage choices) and worn by my handsome dark bay Warmblood Marcus, who was really comfortable in it on hot days.

He sweated less under the straps compared to leather, especially when we did sweaty work such as cross-country schooling or fun rides.

My top tip is to dry off the buckles after the bridle is washed or gets damp or wet in any way, because they did rust on my bridle and I had to stop using it.

Since then I’ve only ever used leather bridles, but I wouldn’t rule out another synthetic in the future.

Double bridles

If you are competing, you may find a double bridle is best suited for your requirements. These are mandatory in some showing classes, such as hunters. A double bridle (sometimes called a Weymouth bridle) has two bits in the horse’s mouth — a curb and a bridoon — and requires the rider to ride with two reins.

Further reading:

- All about horse head anatomy and bridle fit

- Would your horse benefit from wearing a bitless bridle?

- Double bridles explained

Martingales and breastplates

It is not essential that you use a martingale or breastplate (sometimes called a breast girth) on your horse or pony. However, a lot of people choose to use one and therefore I have included them in this list because it is important to understand that they do different jobs.

A martingale is a piece of tack used to control the horse’s head and neck position. It attaches to the girth and bridle to apply pressure should the horse’s head become too elevated.

Riders may choose to use a martingale to prevent their horse from raising their head too high, or tossing and nodding excessively.

There are four types of martingales: a running martingale, standing martingale, bib martingale and an Irish martingale.

A correctly fitting breastplate is designed to help hold your saddle securely in place and stop it from slipping backwards, while ensuring that your horse has complete freedom of movement.

A breastplate attaches to the saddle and the neck strap lies closer to the rider’s hands compared to a martingale, which makes it easy to grab.

Some breastplates have optional martingale attachments, so that they can do both jobs. If your horse doesn’t need to wear a martingale, a breastplate without this attachment is a popular choice with riders to act as a neck strap (I use a breastplate for this reason) and help to keep the saddle in the correct place, particularly when doing high impact work such as cross-country or galloping uphill.

Further reading:

Neck straps

I personally won’t ride a horse without a neck strap. I’m in good company, because William Fox-Pitt — one of the most successful British event riders of all time — once said the same thing about neck straps in a press conference I was reporting at. His horses always wear one too.

A neck strap is very useful to grab hold of if you become unbalanced. I find it easier to grab than the mane, especially if it’s a short mane as that means leaning forward to reach it. Holding on to a mane that has got wet (and therefore slippery) in the rain is not easy either.

For horses who don’t require a martingale or breastplate, their necks look very bare and that makes me a tad nervous. So it’s more of a mind over matter thing for me, and it really does come down to personal preference.

A martingale or breastplate strap isn’t ideal as a neck strap. A separate, purpose-made neck strap is better because it isn’t attached to the rest of your tack and so doesn’t interfere with anything.

I’ve repurposed several old stirrup leathers for this purpose in the past. A neck strap doesn’t have to be expensive in order to do the job.

Reasons to use a neck strap

I find holding a neck strap comes in very handy when I foresee that something tricky to sit to is about to happen.

A loose dog I can hear but can’t see yet, suddenly jumping out of the hedge and surprising my poor horse, who understandably spins or leaps sideways in shock.

This has happened many a time, and by holding the neck strap it absorbs any movement in my upper body should I wobble, rather than the risk of using the reins to rebalance and pulling on the horse’s mouth.

Here are five more good reasons to have a neck strap in your tack room:

- Gives you confidence and a sense of security. This is particularly good for riders who are novices, inexperienced or nervous.

- Protects the horse’s mouth because the neck strap is being grabbed and pulled rather than the reins should the rider become unbalanced.

- Provides extra balance and support on a young or sharp horse. We don’t really want to fall off if we can help it.

- Boosts confidence on unknown horses. I’ve usually got hold of my neck strap until I’m confident said horse isn’t going to try and ditch me.

- It keeps your hands forward. Horses need to use their necks to jump and gallop. If you’re holding the reins short and tight it restricts their movement.

In short, the humble neck strap is an often-under-appreciated piece of tack, yet can be extremely useful for every rider.

Saddlepads and saddlecloths

If you’re going to use a saddle on your horse, you’ll need something underneath it. There are myriad different numnahs, saddlepads and saddlecloths on the market.

They range from simple budget designs to top-of-the-range styles that do all sorts of things, including wicking away sweat from your horse’s back, helping to evenly distribute pressure on the horse’s back and supporting rider (and saddle) balance.

Another perk is that they help to keep the bottom of your saddle clean and hair free.

I think it must feel more comfortable having a piece of soft material directly on your back, rather than a cold leather (or synthetic) saddle.

A saddlecloth is easier to clean than the saddle too – just put it in the washing machine (check the label for washing instructions first).

There is a fashion element to saddlecloths and numnahs, as you can choose a colour to rest the match of your gear. So if you ride in a purple top for cross-country, you may choose to have a matching purple saddlecloth.

Important factors to consider when choosing the correct saddlepad include:

How does it affect the fit of the saddle?

When you have a saddle fitted, make sure it has your chosen numnah underneath because it will influence fit.

What size do you need?

The edge of the saddlecloth or numnah must not finish underneath the saddle, as this can cause pressure points and make your horse sore.

Which material and thickness will suit you best?

This is an important consideration because, as mentioned above, adding a saddlecloth under a saddle will affect its fit. Thicker, fleece-lined numnahs are a common sight in the hunting field.

Lighter, sweat-wicking styles are more common in other disciplines, especially those that take place in summer where your horse is more likely to sweat beneath their saddle.

Which shape do you prefer?

A numnah is typically the same shape as a saddle. A saddlecloth or pad is usually rectangular, so that you can see more of it when it’s under the saddle.

There are half pads available too, which sit under the top of the saddle offering an extra layer of support to the horse’s spine. These are usually used in combination with a lighter saddlecloth.

Do your research

There is a vast range of saddlecloths and numnahs on the market. Eventually you’ll establish which type you prefer.

In my experience, different types and styles will suit different horses better. I must have at least 20 in my tack room. You may need to use them in combination too. Do this with advice from a qualified saddle fitter, so that saddle fit is not negatively affected.

When I bought a GP saddle for Marcus, I noticed that it was rubbing him under the cantle. It was initially fitted by a qualified saddle fitter, who came out to check the fit several times.

We discussed it at length and didn’t think we’d find a saddle that gave a better fit, but we needed to find a solution for it sitting ever so slightly too high at the back.

These were the days when I was very light (good times) so my weight in the saddle didn’t do a lot to help the situation. I solved the problem by riding Marcus in a Prolite half pad on top of a thin Griffin Nuumed numnah.

There was no more saddle rubbing after that. Marcus died 15 years ago and I still have both saddlepads in my tack room (as well as his saddle). They have been worn by various horses since!

Further reading:

- Looking for a saddlepad for hacking? Your Horse tests and reviews 8 different designs

- Looking for a saddlecloth? Your Horse testers rate six for fit, performance and value for money

Girth

Girths are an essential item of horse tack. Its purpose is to hold the saddle in place. The girth attaches to straps on both sides of the saddle. It then wraps around the horse’s body, just behind the front legs.

It is good practice to do the girth up loosely when you first put the saddle on and then gradually tighten it. Before you get on, check the girth is tight enough that the saddle won’t slip as you mount.

Once you’re on board, check the girth again. It will probably need tightening. A few minutes into your ride, check the girth once more. If it feels loose, tighten it again.

How to check your girth is tight enough

To check the girth, try to slip your fingers between it and your horse’s body. If they go in easily, you need to tighten it.

If it feels tight on your fingers, it’s probably OK. This is just a basic guide. The more you check and practice tightening a girth, you’ll find you develop a natural feel for what is right and what is not.

I was taught to tighten my girth by moving my leg forward, so that it rests over the front of the saddle. This leaves the saddle flap clear for me to lift up, feel for the girth straps and pull them up one at a time, until I feel the pin on each buckle lock into a hole.

Other people do it without moving their leg forward. So when you lift the saddle flap up to feel for the girth straps, you lift your leg at the same time.

This has the benefit that if your horse spooks or suddenly shoots forward, you are less likely to lose balance because your legs are still in the right place.

Only undo and tighten one girth buckle at a time. This way, if your horse does shoot forward and you have to drop the girth strap, your saddle is still held in place by the second girth strap. When both girth straps are undone and you let them go, there’s only one place you’re going…

Don’t look down while tightening your girth. You really don’t want to fall off. Learn to do it by feel.

Doing up the girth

Over-tightening a girth too quickly is going to make your horse really cross. Quite rightly, too. Show some consideration by doing it in small steps.

- Aim for the buckles of the girth to be at a similar height on both sides of the saddle. So if the straps on the left side are done up on hole four, it’s good to have the straps on the right side on hole four too so that the saddle is balanced.

- Most GP saddles have three girth straps on each side underneath the saddle flap, even though the majority of girths only have two buckles. Generally speaking, you must always have one buckle attached to the first strap. The second buckle then attaches to either the second or third strap (choose the same on both sides). This can vary between saddles, though, so ask for advice on this when you buy. I once owned a Thorowgood saddle where the first strap was not intended for daily use. I was advised when I bought it to use straps two and three so that’s what I did problem-free for years.

- Some horses are sensitive about being girthed. They may just simply not like it or it might be uncomfortable. Horses suffering with gastric ulcers, for example, can dislike the girth being done up because their tummy is already uncomfortable.

- Alternatively, they may be signalling to you that the saddle doesn’t fit well, their back is sore, or something else. It is a good idea to have these symptoms investigated by a vet and a qualified saddle fitter if necessary. Symptoms may include putting their ears back and pulling an angry face; swishing their tail; fidgeting or kicking out. Tightening the girth gradually over several tries will help.

How to prevent a girth gall

Girth galls are caused when skin or hair gets caught in the girth, causing a painful rub. They are bald patches of skin, which may be bloody. Never ride a horse with a girth gall. Let it heal first.

To prevent one in your horse, stretch your horse’s front legs before you mount. You’ll need to gently guide each leg into a full stretch in front of their body. Aim for enough stretch that the skin behind the elbow is completely flat. This will make sure no hair or skin is trapped under the girth. Do this before every ride.

On horses who are particularly sensitive to girth galls, a girth cover (this is a piece of material, such as fleece, that the girth goes through) can also help to prevent them.

Choosing a girth

Your girth is part of your horse’s everyday tack and plays an essential role in helping to hold your saddle securely in place.

Manufacturers use different materials to help your horse be as comfortable as possible so that they can perform at their best.

There are numerous different designs made from various materials and a variety of shapes and styles. You need to make sure you buy the correct size for your horse too.

Tack room security

According to Oonagh Meyer, Head of Approvals at the British Horse Society, the ideal tack room is either brick or concrete with solid doors that are made of or covered with steel panels and fixed firmly into a strong door frame.

“Hinges and other fixings shouldn’t be accessible from the outside while windows or sky lights should be small and fitted with substantial metal bars or a grille to prevent access if the glass is broken,” advises Oonagh.

Many types of lock are available and, as with house insurance, insurance companies will usually advise choosing a lock that meets BS (British Standard) standards. Often the type of lock, such as mortice or close shackle variety padlocks, will be specified to in order to ensure their policy stipulations are met.

“For feed rooms, unless there’s risk of theft, the main consideration is to make sure that the door can close and has a standard bolt to help minimise the risk of a loose horse getting access to feedstuff – especially in situations where unprepared feeds, such as unsoaked sugarbeet, are accessible,” says Oonagh.

Storing your horse’s tack

Think about how to use the space you have for storing horse tack wisely, especially if your tack room is small.

Saddle and bridle racks on the wall will save space, while hanging rugs rather than folding them on the floor will help them dry more effectively and lower the risk of going mouldy.

“It’s really important that you avoid damp in your tack room as it can harm the leather and stain the appearance of your tack. Cleaning your tack on a regular basis and not allowing it to get too wet when you do clean it will prevent the build-up of mould,” advises Oonagh.

“Keep the room well ventilated and as dry as possible – this could be done by an appropriate heater that could operate on a time switch. If you do use an electrical heater, make sure it’s safe and secure and meets the electrical safety testing requirements to minimise the risk of fire.

“You also need to consider where you might put the heater. Don’t leave it too close to leather or other equipment and make sure you don’t cover the heater.”

Summary

I’ve covered seven items of tack here and there is still so much more to say. If you own a horse, you will also spend a lot of money buying tack. Use it correctly, store it properly and securely, give it the general care and maintenance it requires, and it will serve you well.

Over the years you will find that your supply of tack increases as horses come and go. You could sell on second hand to earn back some of the money you spent.

Alternatively, you might hang on to something in case it becomes useful for a different horse in the future. I do this and I tell myself it’s for this reason, although I’ll confess I am sentimental too.

Storage is an issue, however. I have five saddles sitting on saddle racks in my garage right now, unused because not a single one of them fits my ex-racehorse. Typical!

Images © Shutterstock & Your Horse Library/Aimi Clark/Lucy Merrell