It’s large and it’s complicated, but a horse’s digestive system, much like a person’s, works like a dream when it’s maintained in a healthy state.

Horses are hind gut fermenters, which means their digestive system is very different from ours, a dog’s or even a cow’s — and providing a correct diet is critical for keeping it in good working order.

What is a hind gut fermenter?

Bear in mind that horses don’t have multi-compartmented stomachs like cattle, sheep and goats do. Instead, they have a simple stomach similar to a human’s.

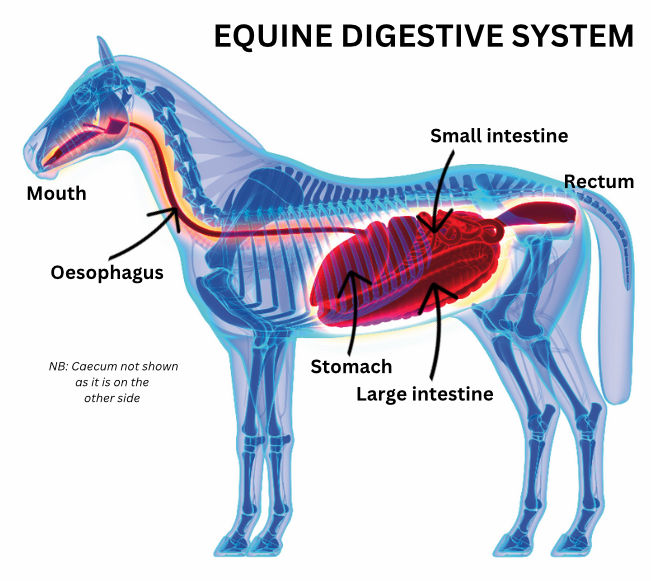

Preliminary digestion occurs first in the foregut (mouth, stomach, small intestine), before fermentation takes place in the hindgut (caecum) — and this is why horses are known as hindgut fermenters.

Several other animals have this type of digestive system too, including rabbits, elephants and rhinoceros.

Managing your horse correctly therefore, and knowing what to avoid and/or look for that can trigger problems — some bigger and potentially more deadly than others — is vital.

Inside the mouth

“A horse’s lips and sensitive muzzle mark the start of their digestive system. Their lips, tongue and teeth are designed to grasp food, which they do effectively,” explains equine vet Sara Fleck.

“Horses can move their jaws from side to side, back and forth, and they also have very moveable tongues and lips — to the point where they could just about form words.”

Once food is in your horse’s mouth, their teeth break it down by crushing and grinding, which releases nutrients from inside the plant cells. Chewing also creates saliva, and adult horses can secrete up to 35-40 litres of saliva per day.

Saliva isn’t gross (!) it’s amazing! This is because it plays a very important role in lubricating ingested food and buffering stomach acid, which is crucial for preventing and managing gastric ulcers. So the more your horse chews, the better.

“Chewed food becomes a soft pulp and is made into a bolus [ball] by the tongue,” continues Sara. “When a horse swallows, the trachea is blocked by the epiglottis to make sure food goes into the oesophagus and not the windpipe.”

The oesophagus is a muscular tube about 1.5m long that transports food from the horse’s mouth into the stomach by rhythmic contractions known as peristalsis.

The bolus then passes through the cardiac sphincter and into the lumen of the stomach. The sphincter acts as a one-way valve, which explains why horses can’t vomit.

Stomach

Once food has been swallowed, it passes down the horse’s oesophagus into their stomach.

A horse’s stomach contains gastric juices, pepsin and hydrochloric acid, which break down food into semi-digested liquid (chime).

The stomach is made up of two types of tissue and the lower section is lined with glandular mucosa, which secretes acid to help digestion.

A horse’s stomach can be divided into the following two parts, separated by a line called the margo plicatus:

- The lower part of the stomach has a glandular lining, and it is here that the acid is produced in response to a complex pathway of stimulatory and inhibitory signals.

- The upper part of the stomach has a squamous lining. It is this part of the stomach that is sensitive to contact with the acid from the lower part which can, in some cases, lead to gastric ulceration.

“The lower area also produces mucus and has protective mechanisms to ensure it’s not damaged.

“The upper section is lined with squamous mucosa, which doesn’t have this protection so is therefore vulnerable if it comes into contact with stomach acid,” explains Sara.

The stomach empties when two thirds full, which means continuous foraging or several small feeds are preferable to large ones.

A horse’s stomach is a muscular organ that’s about the size of a rugby ball (between nine and 15 litres), which is very small.

“This is because horses are designed to trickle feed, eating little and often, and the majority of digestion occurs in the hindgut,” states Sara.

Small intestine

Once processed by the stomach, semi-digested food passes through a valve (the pyloric sphincter) into the small intestine. This is around 25 metres long in a 500kg adult horse.

The small intestine consists of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum, with the duodenum around 1m long.

Enzymes secreted from the pancreas and liver break down food into basic nutrients here. Bile is also secreted direct from the liver.

Some of the protein, fat and non-structural carbohydrates from food will be digested and absorbed in the small intestine.

It is also an important site of mineral absorption, with horses absorbing most, although not all, of their daily requirements prior to the food entering the large intestine.

“While most mineral absorption occurs in the small intestine, research in more recent years has shown that minerals are also absorbed in the large intestine,” states Laura.

Jejunum and caecum

The jejunum is roughly 19m long and the chemical breakdown of food is finished in this part of the small intestine, with nutrients absorbed into the bloodstream to be used by the body or stored in the liver.

“The ileum, around 1m long, is the final part of the small intestine. It continues the absorption of nutrients and controls the passage of partially digested food into the caecum,” explains Sara.

“The junction between the small intestine and the caecum is called the illeo-caecal junction and is a prime spot for tapeworms.”

The caecum itself is 1.5m to 2m long and holds up to 30 litres of fibrous food and fluid.

“Contraction of the caecal muscles results in mixing of the food with microbes that digest tough plant cells via fermentation. This fibre breakdown produces substances called volatile fatty acids, which can then be absorbed and used by your horse for energy,” explains Sara.

Large intestine

Otherwise known as the horse’s hind gut, the large intestine is what makes a horse’s digestive system unique.

As hind gut fermenters, horses rely upon a ‘factory’ of micro-organisms that live within the large intestine to be able to release the energy from a forage-based diet.

“A regular supply of fibre into the micro-organism factory is key to keeping it healthy and functioning well,” advises Dr Laura Wilson, a vet and technical advisor at Dodson & Horrell.

“Regular fibre intake maintains the complex balance in the large intestine, reducing fluctuations in pH and preserving the microbes at optimum levels.”

The large intestine, which is almost 8m in length, consists of the large colon, transverse colon and small colon, and is where most of the water absorption takes place and the remaining food matter is turned into faeces.

“The amount and type of food ingested has a large impact on the amount of water held in the large intestine and the absorption of water and electrolytes,” adds Laura.

“This is important for maintaining gut motility and keeping your horse hydrated (two key factors for general health and the prevention of colic).

The diameter of the large intestine varies from five to 50cm. The pelvic flexure, only 8cm, is where the large colon ‘turns’ to change direction and this is a common site for impactions. The small colon is where faeces form into balls and are evacuated.

“While most mineral absorption occurs in the small intestine, research in more recent years has shown that minerals are also absorbed in the large intestine,” says Laura.

Keeping the digestive system healthy

Mimicking natural feeding and movement patterns is the key to keeping a horse’s digestive system functioning well. Horses with access to ample pasture will spend up to 18 hours a day grazing, while slowly moving around the paddock, which helps to stimulate gastrointestinal motility.

So, where possible, regular turnout is the ideal way to ensure good digestive health in horses.

Other management routines to utilise in order to keep your horse’s digestive system moving include:

- Free access to clean water at all times.

- Add water to feed to mix it, and/or include a soaked bucket to increase water intake.

- Regular dental care to aid chewing.

- Feed food damp and cutting fruit and vegetables into small pieces to avoid choke.

- Introduce any changes in management or diet gradually, to give the microbial population in the system time to adapt. Not doing so increases the risk of colic.

- Feed small, regular meals, alongside high-quality forage. Little and often is key.

- Control parasites (worms) by good pasture management, faecal worm egg counts and targeted use of appropriate wormers.

- If your horse is turned out on sandy soil, consider feeding psyllium as a supplement to prevent sand colic.

- Ensure your horse is getting enough exercise. Movement is key to digestive health. If a horse is retired, there are still ways to get them moving: leading out in-hand, light lunging and increasing turnout, for example.

7 feeding tips

The horse’s hindgut is where fibre is fermented by microbes to produce energy.

It’s important to keep the hindgut healthy, as well as the balance of beneficial and harmful microbes that reside there, as an unhealthy gut can cause problems in the gastro-intestinal tract.

Olivia Colton, senior nutritionist at Feedmark, advises the following to keep the hindgut healthy:

1 Keep your horse hydrated

Dehydration increases the risk of hindgut issues, including impaction. If a horse is reluctant to drink, try giving a soaked feed, adding water to bucket feeds and soaking hay. Offering warm water can also encourage drinking.

2 Provide plenty of forage

Where possible, provide your horse with ad-lib forage. If this isn’t an option, ensure forage is fed regularly. Too little forage increases the risk of colic, gastric ulcers, and other digestive problems.

3 Keep high-starch feeds small

If you feed too much starch in one go, it gets pushed too quickly though the small intestine (where starch should be digested), and so enters the hindgut undigested. It’s then rapidly fermented, producing lactic acid and lowering the pH of the hindgut, which inhibits the population of fibre-fermenting microbes.

4 Add oil for additional energy or condition

When added to the diet gradually, these are much kinder on the gut than high-carb diets.

5 Make any changes to the diet gradually

Abrupt changes can upset the delicate balance of microorganisms in the hindgut.

6 Avoid overusing oral antibiotics and wormers

Though necessary, prolonged use of antibiotics and wormers can harm the population of beneficial microbes within the hindgut.

Resistance to these drugs is also a very real threat to the horse population around the world. Only use antibiotics at the say-so of your vet and follow their instructions to the tee.

7 Try prebiotics and probiotics

If your horse is prone to gut disturbances, or you’ve recently administered antibiotics or wormers, feeding a good quality prebiotic and probiotic supplement daily will help to promote the growth of good bacteria in the hind gut, and promote overall digestive health.

Signs of trouble

Knowing your horse’s normal behaviour is the best way to identify any abnormalities with their digestive system. Seek veterinary advice if you spot any of the following:

- Quidding (dropping partially chewed food from the mouth while eating).

- Coughing or retching after feeding, excessive salivation and food coming from the nose or mouth may indicate your horse is trying to dislodge food during an episode of choke.

- Changes in behaviour, grumpiness when being girthed, weight loss or poor performance — any of these could be indications of gastric ulcers forming.

- Changes in your horse’s manure, as this may reveal information about hydration, efficiency of digestion or parasitic burden.

- Flank watching, rolling, box walking, lack of appetite, vocalising, looking dull/ quiet, diarrhoea, or a lack of faeces are strong indications of colic.

When digestion goes wrong

Any of the following can occur when a horse’s digestive system becomes unhealthy:

Diarrhoea (loose stools)

The most common cause of diarrhoea is a change in diet that affects the water content in faeces, or disrupts/ changes the microbial population within the gastrointestinal system. Other causes may be a parasitic, bacterial or viral infection, a response to drug use, tumours or malfunction of other internal organs. Find out more here.

Choke

Narrow tubes are always prone to getting blocked, and when a blockage of the oesophagus occurs, this is described as choke.

It differs to choke in humans, which generally refers to a blockage of the trachea or windpipe. In horses, most episodes of choke will clear on their own, but in some instances, veterinary intervention may be required.

Gastric ulcers

The risk of gastric ulcers forming is increased by long periods of time spent with an empty stomach.

A food ‘mat’ within the stomach helps prevent acid splashing and damaging the upper, unprotected squamous stomach lining.

Diagnosis is usually by gastroscopy – feeding a long flexible endoscope (camera) down the horse’s oesophagus and into the stomach so the lining can be examined. The time of day you ride and feed plays a big part in preventing and managing ulcers.

Colic

Colic is abdominal pain and may originate from any of the abdominal organs. However, the complex anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract means it’s involved in the vast majority of cases. Colic is broadly categorised into the following:

- Idiopathic/ spasmodic colic

Also known as gassy colic, this is the most common type and occurs when the intestine contracts abnormally, creating painful spasms. Idiopathic is a veterinary term for ‘unknown origin’ as, despite investigation, there are still episodes of colic where the cause is never determined. Thankfully, the majority of these respond to simple medical treatment. - Impactions

This is when a part of the gastrointestinal system is blocked by food material. Impaction colic is fairly common and may resolve with administration of fluids via a stomach tube. Occasionally, larger and more severe impactions will need surgery. Changes in the way a horse is managed is often the cause of impaction colic - Displacements, strangulations and torsions

Displacements happen when one section of the small or large intestine moves to an abnormal location within the abdomen. Strangulating colic describes an episode where the blood supply to a piece of gastrointestinal tract gets cut off. Torsions occur when the bowel twists on itself, cutting off the blood supply. Some displacements can be treated medically but severe ones, and all strangulations and torsions, require surgical correction.

Main image/diagram © Shutterstock & Your Horse Library