Stereotypies (vices) in horses are abnormal, repetitive behaviours that have no obvious purpose or goal, and are a behavioural indicator of poor welfare seen only in domesticated horses — none have been observed in free-ranging ‘wild’ horses.

Behaviour such as crib-biting, box walking and weaving is often called a ‘vice’, which implies the horse is doing something bad or naughty, when in fact they are trying to adapt to a situation they find difficult.

There are many theories as to why horses carry them out, as well as different views on how to manage or prevent stereotypies. It is often believed that horses copy the behaviour from others, or that they can only be inherited.

A long-debated question is whether these stereotypies can be stopped if they have already been learned — and if attempting to do so is a good idea or not.

Resolving a stereotypy (or vice) depends on how long the horse has been performing the behaviour, their age and the type of stereotypical performed. If the behaviour is new and not well-established, you have a good chance of stopping it.

The most important thing is to seek professional help immediately, starting with your vet to rule out any physical problems, followed by a qualified equine behaviourist who will analyse the cause and set up a plan to reduce or resolve the behaviour.

What are horse stereotypies (vices)?

Stereotypies in horses fall into several categories:

Oral stereotypies:

- Cribbing/crib-biting

- Windsucking

- Wood chewing

- Tongue movements (rolling or lolling)

- Lip movements (lip licking and smacking)

- Rubbing teeth against objects or surfaces

Locomotory stereotypies:

- Box walking

- Head movements (bobbing, tossing, shaking or swinging)

- Pacing

- Weaving

- Wall kicking

- Pawing and digging

Self-mutilation:

- Self-biting

- Lunging into objects

Why do horses have stereotypies (vices)?

“Animals often perform stereotypies (vices) when they have no control over their situation,” explains Justine Harrison, a certified equine behaviour consultant.

“Confinement, social isolation, unnatural feeding, over-feeding of grain, constant low-grade pain, the inability to escape frightening or stressful situations, and environments that lack any interest are all contributing factors.

“The behaviour is often developed as a foal. Horses who experienced a traumatic or early weaning are at greater risk of a stereotypy developing. Foals fed grain after weaning and those confined to a stable rather than put in a paddock are also more likely to start windsucking or crib-biting.

“Once the behaviour starts, there is a high risk of it becoming habit as performing the action becomes rewarding for the horse,” continues Justine.

“Research has found that cribbing has a similar effect on the horse’s brain to that of cocaine on the human brain. Horses who have performed certain behaviours over a long period may start to perform them habitually rather than just at a particularly stressful time.

“For example, a horse who has cribbed for many years only when stabled may also start to perform the behaviour when turned out, despite being in a ‘healthier’ environment.

Box walking

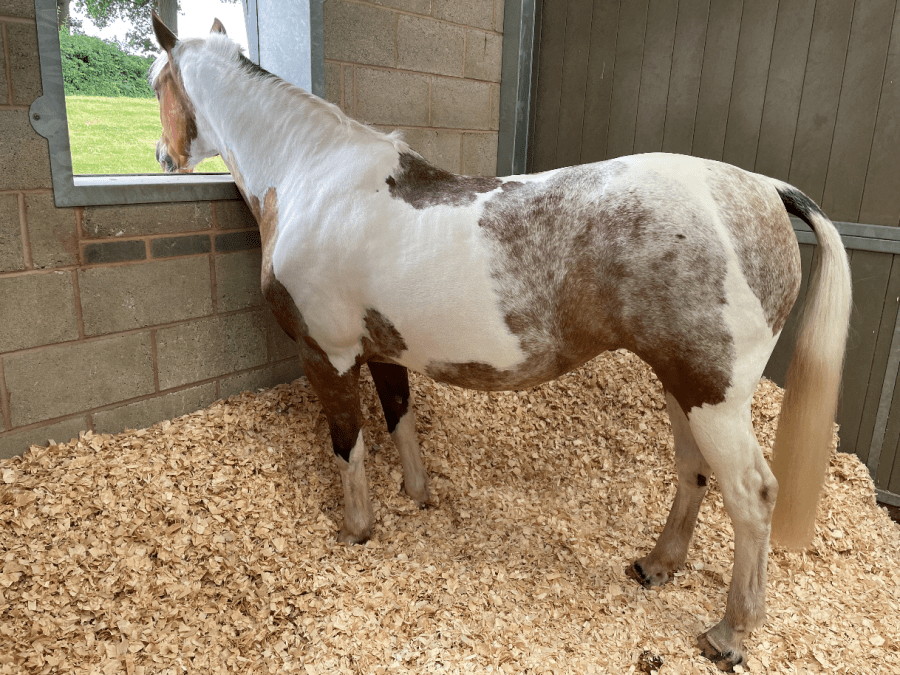

Matilda in her stable

At my old yard, my mare Matilda would box walk in the mornings and it caused me sleepless nights worrying about what damage the constant circling might be doing to her legs and joints.

Unfortunately, the yard had no feeding routine in the mornings, meaning the horses were all fed and turned out at different times and it clearly stressed Matilda out. I’d turn up and she’d be circling like a demon, her bed totally mashed up.

After moving to a new yard, where the horses are all fed at the same time, the box walking completely stopped. Matilda now stands waiting for me to arrive and turn her out.

I think a simple change in management and reassurance that she would be fed with everyone else was enough to curb the behaviour.

Should horse ‘vices’ be stopped?

There’s a saying that prevention is better than cure, and stereotypies are almost impossible to stop completely if they have been performed repeatedly long term. However, the problem may be able to be improved so it is always worth getting expert advice.

Research has shown that performing stereotypical behaviours can reduce stress and it may relieve physical discomfort. Therefore, preventing a horse from performing the behaviour could be detrimental to their welfare.

This was the case of Your Horse editor Aimi’s horse Bee, who became distressed when he was unable to access a surface to windsuck on.

A whole range of devices are available to try and prevent stereotypies (vices), such as anti-weaving grilles and collars to prevent cribbing or windsucking.

Attempting to stop the horse performing a stereotypy does not address or resolve the cause and could result in the horse stressing more, or result in them finding another unwanted behaviour to perform.

Prevention is better than cure, so getting to the root of the problem, and preventing it happening in the first place, or reducing the frequency and intensity, is the far better option.

‘Trying to prevent windsucking caused my horse stress’

Bee was a chronic windsucker

“When my horse Bee arrived at my yard as a five-year-old straight out of racing, he was a persistent windsucker,” says Aimi.

“He would windsuck anywhere he could — in the stable, field and even while travelling in the lorry — and would pause while eating his bucket feeds or munching haylage to windsuck.

“He was a happy, calm horse and very chilled out. Certainly not a ‘stressy’ Thoroughbred; if we had a novice rider at the yard, they would always ride Bee because he was so easy and reliable.

“Windsucking was an ingrained habit and I noticed that he’d become distressed if he couldn’t find a surface to get a good hold of with his teeth.

“He loved a post and rail fence, although maintaining them was an issue. I remember being away for a few days and when I got home discovering that someone had ‘helpfully’ put electric tape along the fence in his field, which meant he couldn’t windsuck. He was walking laps looking for somewhere to bite — he even tried the water bucket!

“The first thing I did was take down the electric fencing. There were no problems after that, and when he moved into a field where electric fencing was the only option, he had a sturdy wooden hay manger in there to windsuck on instead.

“Bee was diagnosed with grade three gastric ulcers which I treated and managed for the rest of his life. I think preventing him windsucking would have caused unnecessary stress.

“He was such a happy, healthy little horse, that I just let him get on with it. He lived with me until he died 12 years later.”

How to avoid horse stereotypies (vices)

To prevent a horse developing stereotypies (vices) it’s vital to ensure that their innate needs are being met. Sometimes, a simple management change may be enough to stop the stereotypy.

There are six key areas to think about when considering your own horse:

1 Friends, forage and freedom

The best way to relax a horse is to give them as much access as possible to turnout, equine company in a friendly stable group and ad-lib grazing or good quality forage. If your horse has to be stabled, ensure that they can see — and preferably touch and interact with — other horses.

2 Routine

Maintain a consistent daily routine. Feed and turnout at the same time whenever possible and keep horses in the same groups (herds). If you aren’t the full-time carer for your horse, it’s worth trying to arrange for the same person to look after them as much as possible in your absence, so that they become familiar.

3 Look for ways to enrich the horse’s environment

Research has found that ‘enriching’ a horse’s environment can provide mental stimulation and prevent boredom. There are some ideas for easy and effective ways to achieve this here — it really does make a difference!

4 Sleep

It’s important a horse feels safe enough to rest and sleep. If a horse is bullied by a field mate, turn them out with a friendlier companion instead. If they are stabled, make sure the stable is big enough for their size and has a deep bed to encourage the horse to lie down, with few distractions. Sleep deprivation can affect horses and their behaviour.

5 Feeding

Access to grazing is ideal, but you can also feed good quality forage as a replacement. Research has shown that horses crib-bite less when fed forage at the same time as their grain feed. Feeding forage-based diets and reducing concentrate feeds is also recommended.

6 Weaning

Foals should be weaned gradually from their dam, keeping stress to a minimum. Weaning should be done no earlier than six months old and ideally later.

Horse stereotypes and vices: the health risks

Performing a stereotypy can put a horse’s health at risk in the following ways:

- Oral stereotypies like cribbing and wood chewing can cause damage to teeth and gums.

- Locomotory stereotypies (weaving, box walking and head bobbing) can put excessive strain on joints.

- Weaving and pacing expend a lot of energy and it can be difficult for the horse to maintain weight.

- Wounds may be caused by self-mutilation or wall kicking.

- Horses with vices may not be welcome on livery yards due to the damage they can cause to fencing and stable doors.

- Vets will often advise against purchasing a horse that performs stereotypies, which can reduce their financial value.

Horses that crib and windsuck are often found to have gastric ulcers. There is debate over whether the horse starts performing these stereotypes (vices) to produce saliva that will buffer stomach acid, which eases the pain caused by the gastric ulcers. Evidence suggests that crib-biters drink more water, which may be for the same reason.

There is also a school of thought that horses who perform stereotypies are so stressed that they are at a higher risk of developing gastric ulcers. This is because stress in horses increases the levels of acid in their stomach.

Images: copyright Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media, Stephanie Bateman & Aimi Clark