Horses love to eat grass, browse hedgerows and pick at branches, however there are several plants that they shouldn’t eat, because they are poisonous for them. It is vital that you as a horse owner recognise and safely remove any poisonous plants that are growing in their field as part of your everyday management and horse care plan.

Plants that are poisonous for horses include buttercups, ragwort, hemlock and foxglove. There are also certain trees that can be troublesome, including oaks and sycamores. All of these (and more) are discussed and pictured below, to help you keep a safe field for your horse to graze all year round.

Poisonous plants for horses: buttercups

Buttercups are common

Buttercups are small, pretty flowers with five bright and shiny yellow petals. They are often described as being “little drops of sunshine”. Buttercups come into flower in early spring and favour fields, pastures, lawns and meadows. The creeping buttercup is the most common variety. It thrives in damp conditions and soil with poor drainage, and it also spreads rapidly.

Eaten in large quantities, fresh buttercups are poisonous to grazing animals like horses as they contain a chemical called protoanemonin in their sap. However, they taste bitter and are largely avoided by horses. Dried buttercups in hay are harmless.

Buttercups are difficult to pull up as they are so widespread. The best way to get rid of them is to outcompete them through effective pasture management so that they stop growing in your field.

Poisonous plants for horses: ragwort

Next time you’re travelling in a car, have a look at the verges, the middle of roundabouts and the central reservation on the motorway. Chances are, they are filled with ragwort — it gets everywhere. This infamous weed has daisy-like yellow flowers and grows up to 1m tall. It favours grasslands, verges, neglected land and overgrazed pastures.

Ragwort flowers in its second year of growing

Seedlings appear from autumn to June and, for the first year, they grow in a rosette form, with spade-shaped leaves that have jagged edges. In their second year of growth, flowers appear in June and the seeds ripen over July and August, before being shed in September. A single ragwort plant can produce 50,000-60,000 seeds, so it spreads incredibly quickly once it goes to seed.

Dealing with ragwort

There is a ditch separating two fields on yard and every spring I pull out multiple ragwort plants (including roots) in their early rosette form. This stops it spreading to the other fields, although I keep an eye out for any others during the spring and summer.

Ragwort is particularly toxic to horses and cattle. Eating between just 1-5kg of ragwort over a horse’s lifetime can cause liver failure and be fatal. It isn’t particularly tasty and horses largely avoid it. When dried in hay, it is more palatable, however, which is one the reasons it shouldn’t be allowed to grow in fields that will be cut for hay.

Ragwort seeds can lie dormant in a field for years, so if you see any plants make sure you pull them up straightway. Not dealing with the problem now will just make it worse in the long run.

What are the signs of ragwort poisoning in horses?

Ragwort rosettes are the early stage of growth

Look out for:

- Diarrhoea

- Weight loss

- Abdominal (stomach) pain, such as colic

- Photosensitisation (this is sensitivity to UV light)

- Jaundice (this is a yellow tinge to the eyes and gums)

- Depression/lethargy or aggressiveness

- Neurological problems such as seizures, losing coordination, continuously moving in circles, head pressing

Ragwort contains Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids, which leads to toxic by-products in the liver when ingested (eaten) by a horse. A horse’s liver can function until around 70% of it is damaged, so if you’re seeing signs of ragwort poisoning, it’s very serious and requires emergency veterinary attention. Ultimately, damaged liver cells cannot regenerate and at this advanced stage treatment is very unlikely.

How to remove ragwort

Ragwort is covered by the Weed Act 1959 and Ragwort Control Act 2003, and landowners have a duty to control its spread. The best way to do this is to manually dig up the plants when they are still at the rosette stage, ideally when the ground is damp. They have deep roots, so use a special ragwort fork and wear gloves to minimise any skin irritation.

You must safely dispose of the ragwort too, ensuring that horses can’t access the wilted plants, and avoid transporting it and inadvertently spreading the seeds. Burning or rotting it down are options. Never leave pulled ragwort in the field. The BHS has lots more advice about safe disposal.

Poisonous plants for horses: horsetail

Horsetail can be up to 90cm tall

There are two different types of horsetail. In the spring, light brown, vertical stems with a small, scaled cone on the top grow up to 25cm high. In the summer, green, fir-tree like shoots grow up to 90cm tall.

Horsetail is a poisonous plant with a deep, strong root structure and it spreads quickly to form a carpet of foliage. Fresh plants aren’t that palatable for horses, but horsetail remains toxic when it is dried in hay. Removing it from the ground is difficult by hand and so the best approach is through careful, long-term pasture management to prevent it growing in the first place.

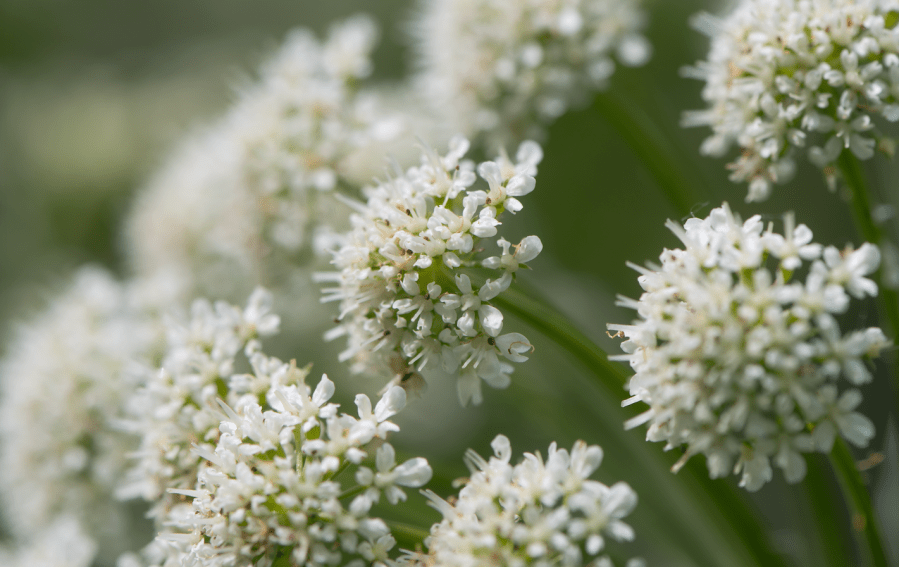

Poisonous plants: hemlock

Hemlock is a tall, upright plant with fern-like leaves and tiny white flowers that bloom in the spring and grow in an umbrella shape. It is most likely to be found in wet areas, such as in ditches, along riverbanks, and on poorly-drained soil.

Hemlock can be fatal in tiny amounts

Hemlock is easily confused with the benign cow parsley, which looks similar. My first pony used to love grabbing some cow parsley out of the hedge to munch on when we were riding! To distinguish between the two, look at the stems. Hemlock’s is smooth and round with purple splotches; cow parsley’s has ridges on it. Hemlock also has an unpleasant, mousy smell.

Although it is largely avoided by livestock, it is highly poisonous and only a tiny amount can prove fatal to horses and humans. In fact, legend has it that it was used as a form of execution in Ancient Greece. So if you see hemlock around your yard or fields, get rid of it immediately.

Hemlock has to be pulled up manually from the root before the plant goes to seed and disposed of appropriately. Don’t burn them, as this releases their toxins into the air. Wear protective clothing when handling hemlock and wash your hands thoroughly afterwards.

Poisonous plants for horses: foxglove

Foxglove: pretty but deadly

Foxglove is a tall plant (up to 2m tall) with purple-pink tubular flowers that bloom in the spring. They are pretty, but don’t be fooled — this plant is poisonous for horses. Most won’t choose to eat foxglove, however it is more palatable in hay and eating just a small amount could be fatal for the horse.

Foxglove contains cardiac glycoside toxins and symptoms of poisoning in horses include changes to their heart rate, breathing difficulties, diarrhoea, dilated pupils, body/muscle tremors and fits. It can be fatal in just a few hours as the toxins immediately damage the horse’s cardiovascular system.

Contact a vet as soon as you suspect your horse may have eaten foxglove. If caught early enough, they may be able to use activated charcoal and mineral oil to flush the toxins out of the horse’s system.

Poisonous plants: deadly nightshade

Deadly Nightshade poisoning isn’t always fatal in horses

Deadly Nightshade grows up to 1.5m, with brown-purple flowers and a shiny black, berry fruit. This poisonous plant contains toxic alkaloids, including atropine. Despite its name, eating it isn’t usually fatal for horses in early and mild cases, providing they are seen and treated by a vet quickly.

Eating Deadly Nightshade will make a horse unwell, with symptoms including dilated pupils, muscle tremors, convulsions or seizures. In more advanced cases, serious symptoms may also include acute haemorrhage, diarrhoea, excessive saliva and progressive paralysis. Vets treat horses suffering with Deadly Nightshade poisoning using compound drugs called neostigmine to reverse the atropine-type symptoms.

Poisonous plants for horses: ivy

Ivy is a cluster of dark green, triangle shaped leaves that grow in vines. It is a common plant and you’ll often see it growing along the walls of houses and winding around tree trunks.

Ivy is a common plant

Ivy contains the toxins triterpenoid saponins and polyacetylene. If eaten by horses, it can cause reactions such as diarrhoea, colic, irritated skin around the mouth, loss of appetite and dehydration.

Oak trees and acorns

While a tree rather than plant, oak trees belong in a list of poisonous plants because acorns are highly toxic to horses. Acorn poisoning is a bigger threat at the end of a long, hot summer. This is because when grass is scarce, horses are more likely to eat them.

Like ragwort, acorns are toxic and horses don’t tend to consume them unless they’re hungry and spend a lot of time turned out. If you spot any acorns at all, it’s best to keep your horse away from them.

“Acorn poisoning can be fatal. If your horse consumes a large amount and shows clinical signs of poisoning, call your vet immediately,” warns equine vet Katherine Hall from Minster Equine Veterinary Clinic in North Yorkshire.

“Toxic acid in acorns causes damage to the horse’s liver and kidneys, sometimes inducing colic.”

Symptoms of acorn toxicity

Acorn toxicity can develop quickly

Acorns fall in autumn and signs of toxicity to look out for include:

- Colic

- Dehydration

- Dull coat

- Loss of appetite

- Frequent urination

- Constipation

- Slow or irregular heart rate

These signs may develop extremely rapidly and death can occur within a further 12 to 24 hours.

“You need to prevent your horse from being able to access acorns that have been blown off trees, so don’t turn them out in a field with an oak tree. At the very least, cordon off the area with electric fencing to keep your horse away,” advises Katherine.

According to BEVA, when a group of horses are exposed to acorns from the same oak tree, only one or two horses will fall ill. This may be because individual horses are particularly susceptible, or that some trees, or even certain acorns, are particularly toxic.

If your field has oak trees either inside or around it, consider letting pigs graze it first. Pigs love acorns and can eat them safely. This technique is used in the New Forest every autumn when up to 600 pigs and piglets are let loose to guzzle the acorns and keep the ponies safe. It’s a win win!

Sycamore trees and atypical myopathy

Avoid grazing horses in fields with sycamores in or close by

Seeds (also known as “masts” or “helicopters”) from the common sycamore tree (Acer pseudoplatanus) produce a toxin called Hypoglycin A, which can remain present in high concentrations in seedlings.

When horses eat these, either by accident or because they are lacking other forage options, some will develop severe and often fatal muscle damage, called atypical myopathy.

Horses with atypical myopathy may present with variable signs, including:

- Muscle soreness, stiffness and weakness

- Difficulty breathing

- Dullness/lethargy

- Muscle trembling

- Colic symptoms

- Brown or dark red urine

Suspected cases of atypical myopathy should receive veterinary attention immediately. Around three quarters of affected horses will die, often despite extensive veterinary treatment but those surviving the initial period will usually go on to make a full recovery.

The only way to prevent atypical myopathy is to prevent horses eating seedlings. This means being able to identify what seedlings look like when they’re on the ground and in the trees, as well as what a sycamore tree itself looks like.

How to lower the risk of poisonous plants for horses

In the short term, the most effective way to get rid of invasive plant species like those listed above is to manually dig them up, but it is important to get the timing right.

Pull up and remove poisonous plants when you see them

“Try to do it as early in the season as possible when the plants are young, the root structure is small and the ground is soft,” says Amy Trewick, an ecologist at Elms Ecology. “However, this isn’t a long-term solution — and it isn’t effective for weeds like creeping buttercups that have such a wide spread. To effectively tackle poisonous plants you need to look at your pasture management.”

Invasive plant species flourish in disturbed, poorly managed soil, favouring paddocks that have been overgrazed, compacted, poached (churned up by heavy animals), or left bare through drought.

“Overgrazing is one of the main problems,” says Kate Still, Head of Farming Programmes at the Soil Association. “Ideally you need to carefully manage grazing and rotate the paddocks as much as possible. Let the grass grow a bit longer; even let certain species go to seed. This gives them loads of root depth, and the long fibres are better for the horse to eat, too. If you can leave at least 7cm of residual grass and then give the pasture time to rest you will protect the soil and avoid creating bare, poached areas.

“In the winter, try to prevent your paddock from getting poached by using mud mats or, if possible, moving field entrances and troughs around,” adds Amy.

How to diversify your horse’s pasture

To prevent poisonous plants, pastures need to be made up of a diverse mix of grasses, herbs and legumes.

“Having a thick sward of robust, deep-rooting species like Timothy, cocksfoot, yarrow and chicory will out-compete invasive weeds and improve the soil structure, making it less susceptible to drought and water logging. Horses will enjoy eating them, too, and they will get more nutritional value from the grass,” adds Kate.

- Consider sowing a herbal ley made up of a mixture of grasses, herbs and legumes. To do so, graze the pasture down quite hard in late spring or ideally late summer. Use a spring tine harrow to break up the ground and then broadcast a herbal ley mix of seed over the top and wait for the rain to come. This should improve pastures quite quickly and, if well looked after, they should only need topping up every five to six years.

- Investigate the condition of your soil. Take soil samples to see what the nutrient and pH levels are like. You can easily order test kits online, and the Soil Association has lots of advice.

- Plants like ragwort and buttercups like acidic soil with a low pH. You can add lime to the soil to bring it up to a neutral level. Weed species also like infertile ground.

- You can boost the fertility of pasture by including things in the seed mix like clovers and other legumes which are natural fertilisers. However, avoid nitrogen fertiliser as this can cause aggressive species like nettles and docks to grow, and it will also make the grass too rich.

Watch out for shrubs

Most poisonous shrubs are more common in gardens than horse paddocks. However, keep an eye out for privet hedges in neighbouring gardens as they can be dangerous even in small quantities. Similarly, rhododendrons and laurel — although rarely eaten by horses — are highly toxic in small amounts. Bracken ferns can also be dangerous, but only if they become a regular part of a horse’s diet.