In all cases of colic in horses, the earlier you spot the signs and call your vet, the greater the chances they have of making a full recovery. Veterinary intervention is always essential, because it can be fatal.

Colic in horses is one of the top reasons for making a claim on horse health insurance policies, especially if surgery is required. In my experience, a horse affected by any type of colic is likely to be at an increased risk of further colic episodes in the future. Colic can occur all year round and there are different types to look for. In this article, I will explain what impaction colic and gassy colic is in horses.

Impaction colic in horses

Impaction colic is a blockage of the intestine, typically due to the accumulation of ingesta (partially digested feed material) within the gut, resulting in a blockage. The impacted food material places pressure on the gut wall and causes gas to build up around the obstruction.

This stimulates sensitive nerves in the gut wall, called stretch receptors, which send pain signals to the brain. It is these pain signals that result in a horse displaying signs of abdominal discomfort – the signs of colic vets and owners recognise.

Impaction colic is particularly prevalent during the winter and accounts for between 8% and 10% of all colic cases. Over time, the impacted food material becomes progressively harder and direr, and therefore more difficult to shift. Most impactions can be resolved with medical treatment, such as oral fluids and painkillers, but occasionally surgical intervention is needed to unblock the intestine.

Early detection of impaction colic is key, but even better is to try to reduce the chance of it occurring in the first place. Knowing how and why impacts occur makes it far easier to identify both possible solutions and the management changes we can implement to minimise the risk.

Causes of impaction colic

The horse’s gut is long and convoluted, with various narrow sections and bends. Impactions typically occur at these locations where the passage of food slows down. The pelvic flexure is one such site. It’s a hairpin-like kink found on the left side of the abdominal cavity near the flank, where the large colon turns back on itself and narrows, and a common location for impaction colic.

As we look at other risk factors associated with impaction colic, it becomes easier to understand why horses are so prone to this type of colic during the winter months. I have seen and treated numerous cases of impaction colic in horses. Below are some of the most common causes:

1 Lack of movement

Shorter daylight hours, poached fields, or lack of winter grazing inevitably result in reduced turnout and exercise time. Movement and exercise are essential in stimulating peristalsis – the contractions of smooth muscle in the gut wall that move food along the digestive tract.

As our horses and ponies spend more time stabled, their guts can become a little sluggish, making impaction colic more likely as the passage of gut contents slows down.

Water is absorbed from food as it passes along the intestine, so the longer food stays in one section of gut, the more water is reabsorbed and the direr the ingesta becomes.

Leaving horses turned out as much as possible will ensure their digestive system is stimulated and kept motile. Horses in good condition can withstand very low temperatures, provided they have access to some form of shelter, so unless grazing is restricted, many horses will be happier and healthier if left outdoors.

2 Reduced fluid intake

Insufficient water can contribute to impactions in two ways:

- First, a lack of dietary moisture quite literally dries out the gut contents, increasing the risk of a blockage.

- Second, dehydration lowers blood volume. Because of this, blood is diverted away from the gut to vital organs such as the heart and kidneys, ensuring they receive an adequate supply of oxygen, water, and nutrients. As blood flow to the gut is reduced, the gut becomes less active and the passage of food along the intestinal tract slows down.

Unfortunately, horses are notoriously fussy drinkers. As the adage goes: ‘you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink’.

However, we do need to make sure the horse can firstly get to the water by breaking any ice that forms on buckets, troughs and automatic drinkers, and we can encourage them to drink.

Cold water is particularly off-putting to many equines, so adding a little warm water or certain flavourings may help to encourage fluid intake.

3 Dietary changes

Another cause associated with colic in horses is the switch from fresh to preserved forage, typically hay or haylage.

Horses are hindgut fermenters and are uniquely adapted to digest fibrous plant material with the help of microbes in the hindgut. Rapid changes in any feed material changes the balance of microbes in the hindgut and alters fermentation patterns.

This results in increased gas production and changes the normal fluid exchange within the colin, increasing the risk of gassy (tympanic) and impaction colic.

Different sources of forage also supply dietary moisture in varying amounts. Fresh grass has a moisture content of around 80%.

Compare this to hay, where the moisture content is reduced to around 12% to prevent spoilage, and we can soon see why fluid requirements for horses often increase in winter, despite the cooler temperatures.

Hydration

As I discussed above, the drier the gut contents, the increased risk of impaction. So, as well as ensuring any changes in forage are made gradually (the horse’s digestive system ideally needs about 14 days to adapt to changes in diet), ensure there’s plenty of fresh water available, particularly if your horse is moving onto forage with a lower moisture content.

It’s easy to feel the inclination to increase concentrate and grain rations to meet the increasing energy demands of keeping warm. However, excess concentrates are more likely to upset the delicate balance of bacteria in the hindgut, potentially resulting in hindgut acidosis or diarrhoea.

In very bleak conditions, I suggest that additional forage is a better way to provide your horse with extra calories for heat production, as fermentation in the hindgut generates heat to help maintain body temperature.

4 Dental disease

Chewing is the first phase of the digestive process and is vital for ensuring proper digestion of fibrous feeds. Older equines often have poor dentition as diastemata (gaps between teeth) develop and teeth are lost. Improperly chewed food, coupled with reduced gastrointestinal motility, means an increased risk of choke and impaction.

Ensure your horse’s teeth are in good condition by having regular dental checks (at least annually) carried out by your vet or a qualified equine dental technician.

In some cases, dietary alterations may be necessary to minimise the risk of impactions. Forage replacers, such as hay cubes or pellets, can be fed in the same quantity as your normal forage source if your horse is struggling to chew properly.

Look to offer around 2% bodyweight total feed per day for maintaining current condition (so 10kg of total food for a 500kg horse).

Access to forage is still important, however, as the chewing action is beneficial to reducing the risk of gastric ulceration, further dental issues, and boredom.

Gassy colic in horses

Gassy colic, otherwise known as spasmodic colic, is a condition where the horse’s bowel becomes hyperactive and spasms. This over-activity of the gastrointestinal tract differs to other more dangerous types of colic, which may be caused by impaction of food material or by areas of the gut becoming twisted.

Clinical signs for gassy colic include:

- Audibly increased gut sounds heard by a bystander

- Food aversion

- Reduced faecal output

- Possible sweating

- Rolling

- Flehmen response (lip curl)

The pain associated with spasmodic colic can appear to come in waves, with the horse becoming painful and then seeming to have some improvement between painful episodes.

This differs to other types of colic, such as displacement or twisting of the gut, where the horse presents as more continuously painful with their distress continuing to worsen.

Any change in routine or diet may trigger an episode of gassy colic, for example box resting after an orthopaedic injury or the sudden availability of turnout in the spring.

As winter approaches, we as owners impose sudden management changes such as changing from grass as the main source of fibre to hay, or from hay to haylage, which is why spasmodic colic can be described as seasonal.

When to call a vet

A veterinary examination should be carried out when any signs of colic arise, as soon as possible. When I assess a horse with potential colic, I check the following:

- Colour of their gums and capillary refill time (ie how quickly the colour returns when I press a finger against the gums)

- Respiratory rate

- Heart rate

- Auscultation of gut sounds.

In an uncomplicated spasmodic colic, these findings are likely to be normal apart from an increase in gut sounds.

I may then carry out a rectal examination to assess if there are any areas of the gastrointestinal tract that are of concern, although this is not a definitive diagnostic test as one can only palpate the caudal third of the abdominal contents.

Most horses with spasmodic colic respond to injections of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antispasmodics that relax the intestinal muscles. Non-response to this treatment may be an indicator that further treatment or surgery may be required.

Case study: ‘She was colicking violently’

One of the scariest things about colic is that it can come out of the blue and develop quickly, as Susie Lear find when her six-year-old mare, May, suddenly began colicking just 30 minutes after a short hack, writes Stephanie Bateman.

May rolled after being untacked, which was unusual behaviour, and then Susie noticed the mare’s breathing was getting heavy. Less than an hour later she arrived at Pool House Equine Clinic, by which time she was colicking violently.

“On arrival there was a team of vets waiting. I got her off the lorry and she collapsed at the bottom of the ramp. Federica, the vet, grabbed May from me and another vet sedated her to calm her down,” recalls Susie.

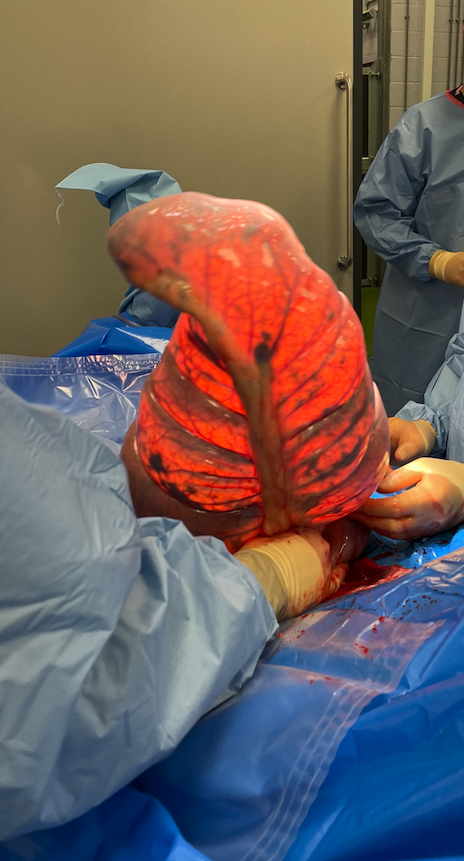

After examination, surgery was recommended and May was operated on.

“The large colon and caecum were severely distended with gas, which was decompressed via needle suction,” explains Federica. “A right dorsal colon displacement was identified, and it was corrected to normal anatomical alignment.” The mare also had an impacted colon.

A sterile abdominal bandage was wrapped around the mare’s stomach and she was closely monitored post-operatively for signs of discomfort, as well as given a course of antimicrobials and anti-inflammatories.

According to Susie, vets believe the reason that May colicked was likely due to a sudden change in temperature, from warm to cold, in the UK, as the equine hospital had another four cases of colic that week too.

REACT to colic

The British Horse Society (BHS) set up its ‘REACT Now to Beat Colic’ campaign to help horse owners and riders identify the early signs of colic. The message is:

- Restless or agitated: for example, the horse repeatedly rolling, sweating, trying to lie down.

- Eating less or droppings reduced: this can include a change in consistency of droppings too.

- Abdominal pain: the horse might kick or bite at their tummy, paw the ground.

- Clinical changes: such as, high heart rate, increased breathing, reduced gut sounds, pale gums.

- Tired or lethargic: a lowered head position or appearing dull and depressed.

“Colic cases can quickly deteriorate so early recognition and prompt veterinary attention is vital to increase the chance of recovery for the horse,” says the BHS.

Main image: © Shutterstock; inset images: © Pool House Equine Clinic