A horse’s joints are key to their ability to be mobile and agile. When horse joints are healthy, they provide a seamless system that allows them to move with ease and they will be sound. However, they can and do become damaged, often leading to significant claims on horse health insurance policies.

The most common form of joint disease is osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative joint disease (DJD). In horses I have seen and treated, osteoarthritis is normally the result of wear and tear in the joint over several years. I see it more commonly is middle-aged to older horses, but it can be found in younger performance horses too.

When your horse works, small amounts of damage that occurs in the normal course of the joint functioning are repaired and the joint returns to normal.

Eventually, though, damage may occur that’s beyond the joint’s ability to repair. This results in inflammation and an increase in the breaking down processes within the horse’s joint, at the expense of the building up for reparative processes.

When the damage exceeds a certain point, cytokines are released by cells within the joint, which in turn leads to further inflammation.

As the joint becomes more inflamed, the synovial membrane reacts by increasing synovial fluid production, causing the joint to become swollen.

As the amount of this fluid increases, the quality of the fluid decreases. By this I mean it becomes thinner and has less shock-absorbing and lubricating ability, resulting in further cartilage damage and worsening inflammation in the horse’s joint.

Types of joints

Each joint is made up of a group of components that work effectively together so that the horse can reach their full athletic potential. Horses have three types of joints: cartilaginous, fibrous and synovial.

- Cartilaginous horse joints are connected by cartilage and have limited movement, for example between the vertebrae in the spine.

- Fibrous horse joints do not move at all; like those that connect bones in the skull.

- Synovial joints move the most and are usually what’s being referred to when equestrians talk about ‘joints’. The fetlock, knee and stifle are synovial joints.

Synovial horse joints

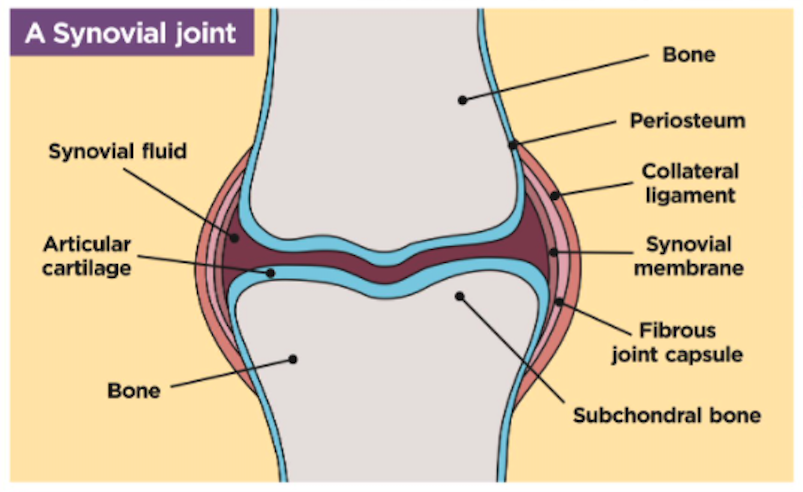

For the rest of this article I am focusing on the synovial joint, which consists of two bones held together by a fibrous joint capsule that’s attached to the surface of each bone.

Within the joint capsule is a synovial membrane that produces and contains synovial (joint) fluid, and the articulating surface of the bones are covered with hyaline (articular) cartilage.

Cartilage covers the ends of the bones within the joint, which comes into contact with each other.

It provides a smooth, almost frictionless surface that allows the bones to move smoothly against each other without damaging the underlying bone.

The ends of these bones are surrounded by a joint capsule which has two parts:

- The outer fibrous portion helps to provide stability in horse joints

- The inner layer is known as the synovial membrane. This membrane produces synovial fluid; this is the thick fluid that fills the inside of the joint.

Synovial fluid has three functions in horse joints:

- To act as a lubricant between the articular cartilage covering the end of each bone and minimise damage that may occur as the two surfaces move against each other.

- To provide shock absorption. It can thicken instantaneously when your horse is moving and their joints are loaded.

- To nourish the articular cartilage (which has no blood supply of its own) by providing nutrients and removing waste.

The collateral ligaments are found in pairs, with one ligament on each side of the joint running between the bones.

Inflammation

The presence of cytokines and of increased synovial fluid is detected by different receptors in the joint, triggering pain signals and resulting in clinical lameness of the horse. If the joint remains inflamed, then further changes may occur, including:

- Thinning of the cartilage, reducing its ability to protect the underlying bone.

- Thickening and stiffness of the bone beneath the cartilage making it more brittle and prone to damage.

- Thickening of the joint capsule which will reduce the range of motion of the horse joint.

- Formulation of bone spurs around the joint as it seeks to repair and strengthen itself and maintain its stability.

- Formation of chip fractures within the joint.

As these changes progress, the joint loses the ability to function normally and lameness will develop.

At best, if addressed early, these changes will result in the joint requiring rest and treatment and being able to return to full function.

At worse, and if left untreated for too long, the joint will develop advanced osteoarthritis and the horse will need to be retired.

Infection

The penetration of a foreign body into a horse’s joint is always a concern and something I see reasonably often as a vet.

Foreign body’s carry bacteria, mud and hair, and can result in a massive inflammatory response causing non-weight bearing lameness to occur within just a few hours.

That’s why it’s important — and I always advise people of this — that any injury to a horse’s joint, no matter how small, should be seen by me/your vet urgently.

If the penetration is relatively small, with no foreign material left inside the joint, it may be possible to manage it by flushing fluid through the joint while your horse is standing still. I will also be injecting them with antibiotics to help prevent/fight infection.

However, if I think there is gross contamination, a general anaesthetic and endoscopic examination of the joint to remove the foreign material will be required.

Depending on your vet practice and what facilities they have on site, this may mean an emergency referral to a nearby equine hospital. Anti-inflammatories and antibiotics will also be given.

If a joint penetration is left for longer than 48 hours, complications can occur and the chances of the horse making a full recovery lower significantly. A potentially septic joint needs urgent attention.

Preventing injury

Although it’s impossible to prevent all injury, it is possible to decrease the risks by taking sensible precautions. I advise the following:

Regular farriery is key

Foot imbalance is significant in the development of lameness as structures are overloaded due to forces being transmitted up the leg unevenly. Also, if you leave your horse too long between visits, then a long toe and an unsupported heel can cause significant lameness.

Ride on suitable surfaces

Choosing a good surface to work your horse on is essential, and it’s vital that the surface is consistent. This is out of your control when hacking, of course, and in fact cross-training on a variety of terrain is thought to be good for a horse’s legs.

The key is to ride at a sensible pace, based on your horse’s fitness levels and ability, and what the going is like.

When riding across uneven ground, be cautious of the unpredictable and changing loads that the legs will be subject to. Be extra careful on hard, rutted ground and boggy ground.

Have a fit horse

Ensure your horse is fit enough for the work you are asking them to do. Many joint and soft tissue injuries occur when the horse is tried and the muscles are less able to support the tendons and ligaments in the limb, causing strains or over-extensions.

Golden rules for looking after horse joints

It’s simple really. If you don’t look after your horse’s legs and joints, you won’t be able to ride them. Here are some of the golden rules to keep in mind:

- Warm up well: you wouldn’t walk out of your house and immediately run as fast as you can, as far as you can, so don’t expect your horse to either.

- Warm down properly: dedicating the last section of your ride, whether schooling, hacking or jumping, to walking will help your horse’s body and muscles cool down, helping to prevent stiffness.

- Use protective wear: are you booting up? Seek advice on which boots best suit your horse’s needs. My advice is choose those that offer strike protection and keep tendons cool.

- Good after care: legs need time to cool off, so remove brushing boots quickly. Consider whether your horse will benefit from turnout after riding and/or cold hosing if they’ve done something particularly demanding, such as galloping or cross-country.

- Watch the ground: riding in deep, boggy ground increases the risk of tendon injuries while lots of work on hard, rutted ground means concussive type injuries are a concern. The ground won’t be perfect all the time, so a bit of common sense is required — no fast galloping on hard ground for example. Research shows that riding your horse on a variety of surfaces is ideal.

- Consider a joint supplement: look for one that contains chondroitin sulphate, glucosamine, MSM, boswellia serrata or green-lipped mussel. Ask for advice if you’re unsure.

Investigating lameness

Modern, portable, high-quality ultrasound and radiography machines, along with a sound knowledge of anatomy and skills in nerve and joint blocking, will help your vet to diagnose joint disease quickly without your horse needing to leave the yard.

In the event that more advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) are required, or if a surgical procedure is needed, your horse will be referred to one of the many equine hospitals across the country.

Certain conditions, such as chip fracture removal or other forms of fracture repair, require surgery. However, several different systemic and intra-articular treatments are available to use in the management of degenerative joint disease.

Treatment options

Cartrophen or Adequan

These are delivered by injection and have a short-term effect on inflamed joints, improving the quality of joint fluid and cartilage and reducing inflammation. They are used once a week for four weeks, they may be given at monthly intervals.

Cartophen and Adequan are often used before or during longer competitions, such as three-day events, to help the horse’s joints when they are under most stress.

Non steroidal anti-inflammatories

Given by injection or orally, mon steroidal anti-inflammatories, such as Bute, work by preventing prostaglandin production, which can contribute to inflammation and joint pain.

Because they are given systemically (which means they affect the whole body), they can inhibit the actions of other beneficial prostaglandins, and if used for too long or too high a dose, lead to side effects such as gastric ulcers or inflammation of the large intestine.

Intra-articular medications

The act of injecting straight into the horse joint itself is not without risk. There is the risk of introducing infection into the joint, failing to get the medication where it needs to be, or the horse reacting badly and damaging themselves or injuring the vet.

Corticosterioids are highly effective at reducing inflammation and arresting the changes that lead to degenerative joint disease. They are the most frequently used type of joint medication and must be used carefully. If used too often, they can lead to thinning of the articular cartilage and, subsequently, worse lameness.

Hyaluronic Acid is a natural component of horse joint fluid and may be injected into joints alone to improve the quality of synovial fluid. Or, more frequently, it may be used along with a corticosteroid to prolong the anti-inflammatory effects.

It may also be given intravenously when it can have a short term anti-inflammatory effect on any inflamed joints.

Polyacrylamide Hydrogel is a relatively recent arrival in the equine world. When injected into a joint, it mimics the viscoelastic action of synovial fluid and provides a synthetic form of lubrication, improving joint function and comfort.

Regenerative medicine

The use of products derived from the blood of the horse, which contain natural anti-inflammatory molecules that block the effects of cytokines, is now widespread. These products also contain growth factors that can stimulate additional repair within the joint.

Commonly used products are IRAP and Pro-Stride, both of which are made by extracting and then processing the horse’s own blood and turning it into a product that is then injected back into the diseased joints.

It produces no unwanted side effects, such as laminitis, and because the product is entirely natural, there’s no risk of falling foul of any anti-doping rules for those horses who compete under rules.

Other regenerative medicine products include platelet-rich plasma and stem cells. These are sometimes more frequently used in the presence of significant soft tissue inflammation such as collateral ligament injuries.

Joint treatments have a common goal — to repair normal function. Whether or not this is possible depends on the degree of damage in the first place, and what the joint is asked to do following treatment.

Images: © Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media/Sally Newcomb. Diagram: © Your Horse Library/Geoff Johnson Design