If you’ve ever heard or said the term ‘locking stifle’, you’re referring to the patella, which plays a vital role in a horse’s hind leg action and has a unique locking mechanism to enable them to sleep standing up. Otherwise known as the kneecap, the patella is a round, flat bone in the tendon part of the quadriceps muscle of the thigh.

Three ligaments are attached to it and it sits in a depression on the femur (the trochlear groove) and slides up and down within this groove as the hindleg moves. This action enables the knee joint or stifle to operate like a hinge, allowing the leg to flex and extend but not to move sideways. Thanks to the attachments to the tibia, the three ligaments (the lateral, middle and medial ligaments) help to keep the patella in place. They are also involved in the patella’s locking mechanism.

How the horse’s patella works

The three ligaments around the patella enable it to lock in place. Usually the patella glides freely within the trochlear groove, but when it’s locked the medial patella ligament becomes hooked over the end of the femur so that the stifle can’t be flexed. This feature causes the stifle to become immobile and allows the horse to rest in a standing position without using lots of energy in the process. The horse can then rest one leg at a time and can remain standing for long periods, including when they sleep.

To release the lock, the horse shifts their weight on to the other hindlimb, which causes the thigh muscle to pull the patella back into place on the original resting limb. When the leg is locked, it can easily be ‘unlocked’ if the horse needs to run from danger. This is important when you consider that in the wild, horses are a prey animal.

The patella locking mechanism makes up part of the reciprocal apparatus, which involves the muscles and tendons on either side of the tibia. This ensures that when the stifle is flexed, the hock is also flexed, and when the stifle is in extension, the hock is also in extension. This process allows the horse’s stifle and hock joints to move in unison. The horse can support their weight while standing and resting, and the hindlimb moves efficiently and smoothly during exercise.

The reciprocal apparatus uses tendons and ligaments rather than muscles, meaning that the lower limbs don’t get tired as easily. The horse’s limb continues to move with the same rhythm and strength for sustained periods of time.

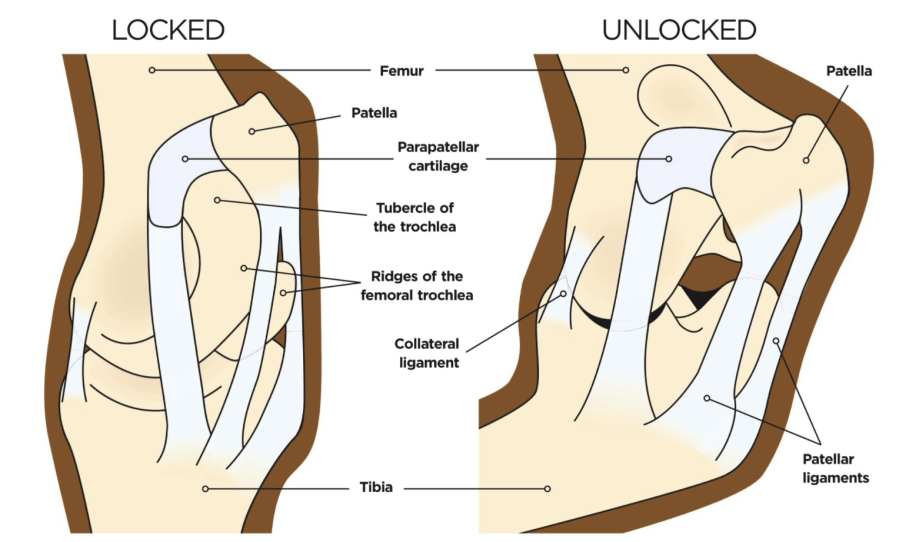

The following diagram shows the patella when it is in the locked and unlocked position:

What can go wrong with a horse’s patella?

1 Upward fixation of the patella (locking stifle or locking patella)

Although the patella locking mechanism is a helpful adaptation in the horse, sometimes it can go wrong, and this results in the patella being stuck in the locked position. This occurs when the hindlimb is extended back further than normal and the limb becomes stuck in extension.

Locking stifle is more likely to occur in horses with particularly straight hind limns and especially in young horses and ponies with poor muscle condition. In these cases, the weak thigh muscle fails to pull and release the patella.

If there has been trauma to the stifle region, in particular to the patella or its ligaments, it might become more difficult for the patella to be moved around and it may therefore remain in the locked position. Often a locking stifle becomes more obvious when the horse is stabled, and they will be seen holding and extending the limb back while flexing the fetlock.

Prognosis for a locking stifle

If a horse is diagnosed with locking stifle, the horse can be given an exercise programme to follow. The aim of it will be to build up the horse’s thigh muscles. Exercise may include daily lunging, or walking up hills, and as much turnout as possible.

A conditioning and exercise programme is usually most effective in young horses. In other instances, surgery may be required. The prognosis for locking stifles is good, however, as most cases respond well to management.

Managing a locking stifle

One four-year-old gelding I met has showed signs of locking stifle since the age of two. It was particularly a problem when he was stabled and his owner described him as “looking like a ballerina”. As the horse was so young and still growing, I recommended pole work exercises, lunging and hill work to strengthen his thigh muscles. After a few months of this, I was told that signs of a locking stifle were less frequent.

The horse still suffers with a locking stifle every now and then — usually in winter when he’s stabled overnight and less so in the summer when he’s turned out more and exercised frequently. He never appears distressed when his stifle becomes locked and the owner back him up a stride before bringing him out of the stable if she thinks there might be a problem. Interestingly, as the horse’s dressage skills developed and he did more lateral work, this seemed to help reduce the number of locking stifle episodes too.

2 Luxation (dislocation) of the patella

Usually the trochlear groove is deep enough for the patella to stay within it, but if it’s too shallow the patella will slide sideways out of the groove. This condition tends to be seen in miniature breeds or in foals and is thought to be an inherited condition.

An affected horse can be seen standing in a crouched position, unable to extend their stifle. They may also have a stiff gait. Surgery is required to treat the problem to ensure the patella stays within the groove. Because the condition is hereditary, breeding from affected animals is not recommended.

3 Fractured patella

A fractured patella can be caused by a kick to the stifle area, the leg hitting a jump, or getting stuck while trying to climb over a gate. Generally, the horse will show signs of lameness, with heat, pain and swelling around the area. There may also be a skin wound indicating where the injury occurred.

If I suspect a fracture of the patella, I will take X-rays of the area to see the extent of the injury. In some cases, box rest and pain relief will prompt healing, but she horses will require surgery to remove fragments of bone, or to repair large fractures..

4 Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis can occur following one of the conditions mentioned above, or after trauma or injury to the joint. The horse is likely to be lame and there may be swelling. X-rays will be taken to assess the area, checking for fractures or bone fragments. Steroid injections into the joint around the patella can be given and, as part of the recovery, controlled exercise programmes are common practice.

If the horse doesn’t have severe osteoarthritis, it can often be managed with anti-inflammatory medication or joint injections, but if the disease is advanced it is probably unlikely that they will return to full work.

5 Other patella problems

There are many other injuries that can affect the stifle joint, but the key point is to identify that the horse isn’t moving correctly and ask your vet to examine the affected leg. They will perform diagnostic tests, such as X-rays, to assess the patella and the stifle joint. Once the problem has been diagnosed, a plan can be put in place to manage or treat the condition.

Main image: copyright Shutterstock; diagram: copyright Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media