Lameness is one of the main symptoms of navicular in horses and both front feet are usually affected, which can make it difficult for owners to identify. Good regular hoof care is vital for helping to prevent it, as well as managing horses with a positive diagnosis.

When both feet are affected equally by navicular, there is no obvious nodding of the head when the horse is trotted up in a straight line. Instead, the stride may look short and choppy.

It may be easier to identify lameness by lunging the horse on a circle, because the inside leg takes a greater strain and any pain this causes the horse will trigger head nodding.

Symptoms of navicular in horses

Navicular syndrome is a debilitating condition responsible for over a third of chronic lameness in horses and its symptoms can be so discreet that it creeps up on owners unawares.

Symptoms of navicular in horses may start as an intermittent low-level lameness that resolves with a couple of days rest.

In the early stages, some horses may “warm out” of the lameness, which means they appear to be stiff as they leave the stable and improve with exercise.

Other noticeable symptoms of navicular in horses are frequent stumbling and/or pointing one foot at an angle. A keen eye may notice that the horse subtly puts their toe to the ground slightly before the heel lands when walked on a flat surface and viewed from the side.

This toe-heel action occurs because horses with navicular syndrome feel pain in their heel region.

Diagnosing navicular

Precise diagnosis of navicular is based on the characteristic symptoms and signs together with a lameness work-up by your vet.

Your vet may employ a number of techniques in locating the source of pain, including injecting local anaesthetic around nerves supplying the foot or into joints within the foot.

These nerve blocks can narrow down the region the pain is coming from, but they must be interpreted with care as the anaesthetic can diffuse and affect other areas too, not just those areas it was intended for.

If navicular syndrome is suspected, X-rays can be taken of the foot. These focus on two things:

- The shape and balance of the foot, and how the external appearance of the hoof relates to the internal positioning of the bones within the hoof. Here vets look at the angles of various structures in the foot to determine what biomechanical forces are applied to the hoof.

- Appearance of the navicular bone itself is also evaluated. A number of changes seen on the bone, such as new bone formation or loss of bone density, can indicate navicular syndrome. It is worth noting, however, that some horses’ X-rays show changes to their navicular bones and yet have no symptoms or lameness, while others who do have navicular syndrome show no evidence of this on X-ray.

This is what navicular in horses is

It is useful to understand that navicular is not a single disease per se, but more of a ‘syndrome’ in horses where multiple structures may be implicated.

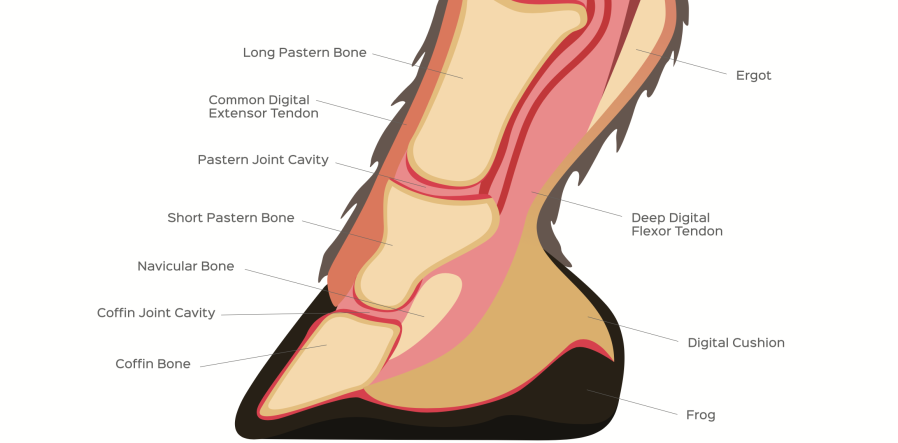

The navicular bone is a small boat-shaped bone, sitting at the back of the hoof and tucked behind the larger pedal bone (sometimes also called the coffin bone). It’s held in place by a number of ligaments.

The navicular bursa is a sac filled with lubricating synovial fluid positioned at the back of the bone to cushion the deep digital flexor tendon as it passes over the navicular bone.

Pain associated with navicular syndrome can come from damage to any of these structures supporting the navicular bone, as well as direct damage to the bone itself.

Historically, navicular was attributed to interruption of the blood supply to the navicular bone: this is ‘the vascular theory’. This has gone out of favour as a major factor in navicular syndrome but treatments geared towards restoring the blood flow do have some effect, so opinion is still divided.

The navicular bone takes a lot of biomechanical strain when the horse moves. As the deep digital flexor muscle contracts, the tendon tightens and pushes on the navicular bone. To help prevent damage to the tendon or navicular bone, a thick layer of fibrous cartilage protects the bone, and this may be worn down in cases of navicular syndrome.

These horses are most at risk

To make some generalisations, navicular is more often found in horses with a certain foot conformation: overlong toes and collapsed heels.

There is believed to be a genetic component as navicular syndrome is more common in certain breeds such as warmbloods, thoroughbreds and quarter horses. It rarely affects ponies.

A susceptible conformation subjected to repetitive concussion can lead to a degenerative processs within the foot.

The average age for a horse to develop signs of navicular disease is between seven and 11 years. This perhaps reflects the degenerative nature of the problem caused by wear and tear. However, I know that it can occasionally be seen in horses as young as three.

This is how navicular is diagnosed

Diagnostic techniques taken from human medicine have been adapted for horses. This has taken the diagnosis of navicular syndrome to a new dimension.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT) allow vets to take a closer, detailed look at all the structures in the hoof: bone, cartilage, tendons and ligaments. This means that we as vets are able to diagnose soft-tissue injuries previously unseen on X-ray.

MRI scanning is restricted to referral hospitals. Conditions that once upon a time may have been put down to navicular can now be more accurately diagnosed. These include fraying of the deep digital flexor tendon within the hoof or damage to the supporting ligaments of the navicular bone.

This way of viewing the foot are very useful but also expensive (in excess of £1,000). Some insurance companies don’t cover their cost fully, so it’s worth bearing this in mind if you choose to go down this route.

Preventing navicular

It can be hard to see how you can possibly prevent a condition like navicular developing when so many factors contribute to it. However, some simple rules do apply.

- Good, regular routine farriery every 4-6 weeks will help reduce the load on the heels and over the navicular bone.

- If your horse historically ‘feels’ the ground, it is common sense to avoid riding at speed or jumping on hard ground. The repetitive concussion of riding on hard ground is inflicted on the heels and navicular region and can be enough to encourage the onset of this degenerative condition.

- Avoid tight circle work unless on a soft, level surface.

- Be sensible if the ground is unsuitable. If you turn up at a competition and the going is too hard, be wise enough to put your horse back in the lorry, no matter how far you’ve driven, and curse the good weather on the way home.

Treatment options

Treatment options for navicular syndrome have come a long way. Firstly, the treatment should be geared towards the actual structures identified as involved in each individual case. For example, a soft tissue injury may require an extended period of box rest (over six months in some cases).

Corrective farriery is a vital part (if not the main piece) of the treatment jigsaw for navicular. Teamwork between you, your vet and your farrier can assist in keeping your horse sound and comfortable.

The aim is to re-establish the best foot shape possible to cope with the demands of work and to fine-tune the forces placed on the foot to avoid over-loading the vulnerable areas, namely the rear third of the hoof.

Why hoof balance is key

Hooves should never be allowed to grow overlong and so make a date in your diary for shoeing every four to six weeks.

The foot should be balanced from side to side, the toes shortened and good heel support provided. This may take the form of a rolled toe or four-point shoe, bar shoes or 10° heel wedges.

Some farriers like to use silicon pads for their anti-concussive effects.

Careful use of oral anti-inflammatories may help, such as phenylbutazone (bute). It’s important not to make the horse so comfortable that it worsens an existing injury.

Vets often inject an anti-inflammatory, such as steroid, directly into either the coffin joint or the navicular bursa.

Injecting into the navicular bursa is the trickier but more effective option.

In one study, 60% of horses were still sound after two months following bursa injection, compared to 34% that had their coffin joints medicated.

Other treatment for symptoms of navicular in horses

A newer treatment to the UK is the anti-arthritic drug tiludronate (Tildren™). It helps to switch off cells involved in arthritic processes.

Tildren is given as an intravenous drip and has been effective in treating some forms of navicular where bony remodelling is a feature.

In some cases, Isoxsuprine has been used successfully on the basis of the restoring good blood flow to the feet and satisfying the vascular theory of navicular.

As a last resort, some owners opt for neurectomy, which is a de-nerving operation. This is a surgical procedure to numb the hoof by cutting the nerves that supply it.

It is often used as a last resort as there are many risky consequences associated with de-nerving, such as dangerous stumbling or development of severe foot abscesses.

Sometimes the nerve grows back or forms a painful lump called a neuroma. Many governing bodies, such as the FEI, do not allow de-nerved horses to compete.

Despite this, for some horses and owners it proves to be a valid option and they continue to live a happy, pain-free life for many years.

Main image and diagram © Shutterstock