Sesamoiditis can cause pain and lameness in horses. There are two sesamoid bones found at the back of each of the horse’s fetlock joints which are attached to ligaments that help move the leg. If these bones are damaged, it can have serious consequences for horse health, and these vulnerable bones are susceptible to catastrophic injury.

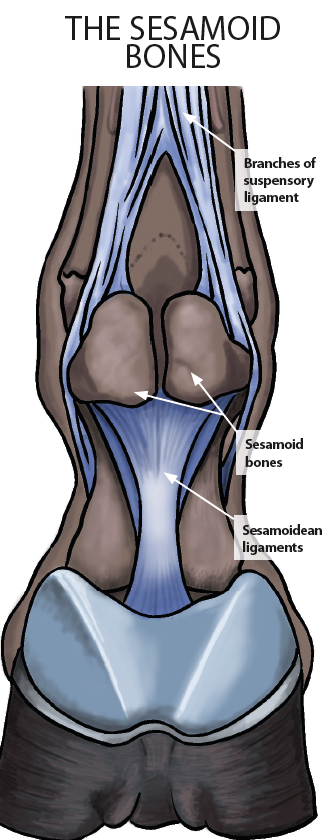

Diagram shows the location of the sesamoid bones. Credit: Your Horse Library/Geoff Johnson

The location of a horse’s sesamoid bones makes them vulnerable to injuries, some of which can be very tricky to repair (see diagram, right). They don’t have the blood supply that many other bones do, because they lack any musculature around them that can lend blood supply. They also don’t have a periosteum (the soft, protective tissue covering bone). Without these, they find it hard to heal themselves when injured.

What is sesamoiditis in horses?

Sesamoiditis in horses is a condition that occurs when the sesamoid bones become inflamed and cannot work properly. It is most often seen in athletic horses such as racehorses, who often place extreme pressure or stress on the sesamoid bones during exercise. In a galloping racehorse, the fetlock can sometimes extend to the point that the sesamoid bones make contact with the ground. In some cases, when the pressure is too high, this can cause the bones to shatter, resulting in the horse needing to be euthanised.

Like any bone, sesamoids can fracture if overstressed. Horses carrying too much weight or those with particularly long pasterns and low heels are predisposed to developing sesamoiditis. It has also been suggested that some horses have a genetic predisposition for sesamoiditis, especially those with a deficient blood flow to the sesamoid bones

Symptoms and common causes of sesamoiditis

As the sesamoid bones are in an awkward place, repairing them can be tricky, so it’s vital to contact your vet if your horse shows any signs that could be related to sesamoiditis. The sooner it is treated, the better the prognosis. Signs to look out for include:

- Sensitivity to pressure on the sesamoid bones

- Lameness

- Warmth felt on the fetlock

- Swelling around the fetlock joint

Sesamoiditis is caused when stress is exerted on the sesamoid bones during high intensity exercise such as jumping or galloping at high speeds. In horses with reduced blood flow to the sesamoid bones, this can be aggravated by concussive joints and stress on the ligaments, causing pain, inflammation, and demineralisation of the bone. Poor conformation and feet that aren’t correctly balanced also predispose a horse to the condition.

Diagnosing sesamoiditis in horses

Diagnosing sesamoiditis in horses can be difficult because, over time, injuries can weaken bones before they actually fracture. It then takes more time for the fracture to show up on imaging tools. When diagnosing sesamoiditis, your vet will perform a thorough physical examination of your horse, after which they may decide to nerve block. This is when your horse is given an injection with a local anaesthetic to block out any pain below the point of injection for diagnostic purposes. Diagnostic anaesthesia isn’t guaranteed to give a decisive diagnosis, but it can help narrow down the search for a possible sesamoid injury.

Next, your vet may opt to take radiographs (X-rays). These don’t always show any damage; if this is the case, waiting 10-14 days then redoing the X-rays will give the sesamoiditis time to appear. During the 10-14 day waiting period, the horse’s movement should be limited. If a definitive diagnosis still can’t be reached, the next step would be an MRI scan, which will give a much clearer picture of the area. This might show up problems in the soft tissue in the area.

Treatment options

Once a definitive diagnosis of sesamoiditis has been made, your vet will discuss treatment options with you and set in place a plan for your horse. These could include hot and cold therapies or poultices on the fetlock to help reduce the inflammation. Placing your horse on box rest or in a small paddock to allow the condition to rest is vital. This may be required for around 30 days, with hand-walking for up to 60 days, to prevent your horse reinjuring the sesamoid bones. After the 60 days, your horse can go on limited turnout until your vet gives the all-clear to return to normal activity.

Other options include special shoeing — a heart bar shoe or an egg bar shoe — to support the back of the joint, which will reduce the stress on the ligaments and the sesamoid bones. Anti-inflammatory medications may also be prescribed, as well as intra-articular treatments of the fetlock joint to reduce inflammation in the joint.

Another possible treatment option is a medication called Tildren, which is a bisphosphonate that prevents destruction of bone. It is a one-off intravenous infusion or injection.

Prognosis for horses with sesamoiditis

Sesamoiditis in horses can be treatable, especially if found early enough. The recovery time can seem long, but resting your horse and making sure they do not overexert themselves during exercise is important to making a full recovery. It can be difficult to prevent sesamoiditis, especially in athletic horses, but you can help prevent the condition by limiting the amount of exercise performed on hard surfaces and by managing your horse’s weight so he is not placing excess load on the joints. Also, by acting quickly when you find signs, you will help your horse recover more quickly.

True life: how my horse survived a fracture to his sesamoid bone

Ex-racehorse King Muro recovered from a fractured sesamoid bone. Photo by Aimi Clark

When my ex-racehorse King Muro fractured a sesamoid bone in the summer of 2019, it spelled the end of a successful National Hunt career (he won seven times under Rules and earned more than £45,000). X-rays revealed a proximal fracture to the outside sesamoid in the then 10-year-old’s right fore and he was prescribed box rest to give the bone time to mend. I took King on loan 18 months later, when he had fully recovered and was sound.

The key was managing his injury to prevent it causing him further pain, which included remedial shoeing and heart-bar shoes to improve his foot balance and lower the risk of tweaking the old injury or sesamoiditis occurring. King loved hacking, and we had a lot of fun doing #Hack1000Miles together, but I was always mindful to carefully manage his workload.

This meant no fast work or jumping on hard ground, and limiting how much trotting we did on the road. I have been fortunate to own a lot of ex-racehorses over the years and I’ve always been wary about looking after their legs, so this was normal practice for me.

Sadly King and I had less than a year together, as he had to be euthanised as a result of a different injury. Our time together was brief but so much fun, and his old sesamoid injury wasn’t a problem with careful management. I really miss him.

Thank you to vet Sue Taylor BVMS MVM MRCVS for providing the veterinary know-how in this article. Sue runs mixed animal veterinary hospital Connaught House in Wolverhampton. She is also a racecourse vet at Wolverhampton, Uttoxeter, Haydock and Aintree, an examiner for the Worshipful Company of Farriers, and trains point-to-pointers and hunter chasers. Main image by Shutterstock.