Six words make up the Scales of Training in dressage and they apply to all horses and ponies, whatever level you ride at. Whether you dream of turning your dressage horse into the next Valegro, or are simply seeking a training guide to teach your steed to move better on the flat — and in turn over a jump — the foundations are the same.

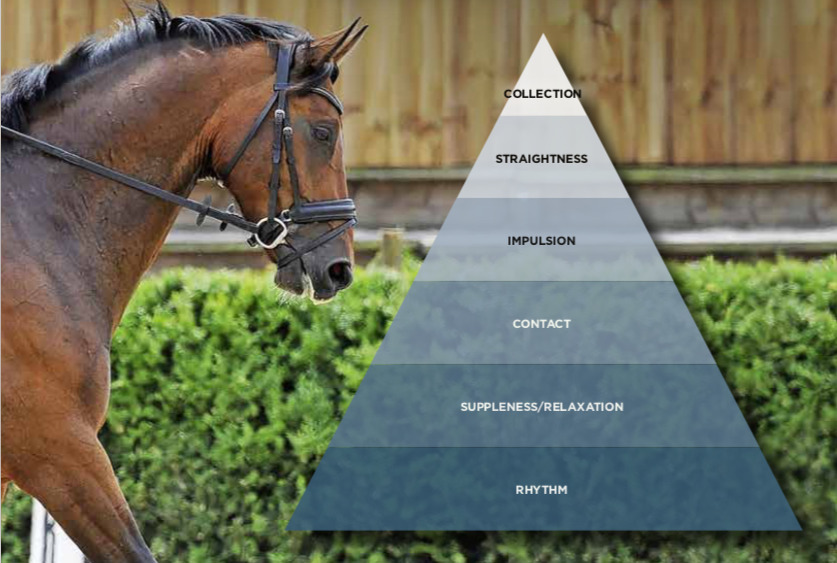

The six elements of the training scale interact with and depend on one another — they don’t work alone. It helps if you visualise the scale as a pyramid, with each layer representing one scale.

It’s important to achieve each stage before moving on to the next. You can’t, for example, achieve contact without having rhythm and suppleness in place first.

However, the six layers shouldn’t be treated as a list to work your way through and the lower rungs should be revisited throughout your horse’s training.

The Scales of Training

The dressage training scale is:

- Rhythm (bottom of pyramid)

- Suppleness

- Contact

- Impulsion

- Straightness

- Collection (top of pyramid)

This linear format should only be used as a guide. In practice, the dressage training scale is more a set of training goals or principles than a scale. The concepts are much more complex than a single list is able to express.

Each level is interconnected and you may find that you need to spend longer on one element with certain horses, but not with others. It comes down to the individual horse’s temperament and natural abilities.

How the Scales work

The dressage Scales of Training can be further subdivided into three categories:

- The first three scales — rhythm, suppleness and contact — are part of the first ‘familiarisation phase’. This is where your horse learns to hold themselves properly when carrying a rider, using their core, being relaxed, and listening to the rider’s aids while seeking an elastic connection.

- The second phase involves both impulsion — the contained power of the horse — and straightness. When a horse is crooked, it will be more difficult for them to stay balanced and develop impulsion. This is why you need to teach them to use their hindquarters effectively.

- The third phase builds on the second phase, as your horse develops the carrying power of their hindlegs, leading to collection. As they progress in their training and hone the necessary muscles, they will carry more weight on their hindquarters, in turn lightening their forehand, thus giving them more freedom to move their shoulders. This will make the horse an easier and more athletic ride.

How dressage judges use them

The six scales are not just a guide for how horses should be trained. Judges also use them to determine the quality of a performance during a dressage test.

Judges are trained to assess a horse’s way of going against the level of test they are performing. This is why, although you may score in the high 60s at novice level, when moving up a level your score may go down to the 50s.

This is purely because your horse’s way of going has not yet developed enough to warrant a better mark at that higher level.

The first thing a judge will look for is whether a horse is working evenly in each pace and with a constant tempo, both of which come under the first foundation: rhythm. The judge will then move on to suppleness and work their way up the scales pyramid.

Scale 1: Rhythm

Many riders struggle with achieving rhythm. The word ‘rhythm’ is derived from the Greek word rhythmos which means ‘measured motion’. You could also describe rhythm as the regular occurrence, or timing, of a beat. In equestrian terms it relates to the regularity of footfall in any pace.

“Measured motion relates to each step being of equal length in every pace. In order to achieve this, the horse needs to be in balance and self-carriage,” explains international dressage trainer Ian Woodhead.

“Horses develop their strength through progressive training and, as they strengthen, they therefore improve in their ability to carry themselves in more complex movements.”

Scale 2: Suppleness

A supple horse turns their head, neck and haunches in either direction with equal freedom and range of motion. This the second scale to achieve in dressage training, and it is only achievable when your horse is working in a regular rhythm.

“As riders we are often stiff in places we don’t even know about and many of us have unconsciously been compensating for years. Horses are just the same, yet we often expect them to be able to work on a 20m circle on either rein and stay balanced and relaxed throughout,” says Ian.

“Suppleness and having equal range of motion down both sides of the body will therefore enable your horse to move with freedom, both in a straight line and in the more complicated school movements. For this reason, achieving a relaxed and supple horse should be a priority for riders in all disciplines.”

Scale 3: Contact

Contact is what the rider feels through the reins and should come from the horse’s hindleg, through to the mouth. The rider must learn to ride the horse in front of the leg to the contact, and learn to regulate the degree of contact they are allowed to have.

Although it may seem basic, Ian advises that a good starting point is running through the process of asking for a contact and look at what your horse does to accept it.

- Begin by riding in walk. Ride between medium and extended walk, using a light and consistent rein, and testing that your horse is attentive to the rein aid before you start work.

- Your horse will seek a steady, inviting contact, and will engage their hind end and round their back muscles. Once you feel that engagement and acceptance, maintain it for long enough to truly feel it take effect.

“Contact is about much more than just head and neck position,” explains Ian.

“Once you feel the difference that the whole body connection makes, work your way up to trying circles and transitions while maintaining that elastic and effective contact.

“When you have a good contact with your horse in front of the leg and in balance, you should be able to give your hand forward for two or three strides (giving and re-taking the rein) without any change to the outline or speed of the pace that your horse is working in,” continues Ian.

“If the outline or speed changes, you have allowed your horse to rely on your hand, which means you’re ‘holding’ the contact rather than ‘creating’ the contact — and this is incorrect. You need to be able to ride your horse in front of the leg to be able to create a good contact.

Three types of contact

When training your horse to understand the contact, there are three types of contact you can work with:

1 Perfect contact

This is when the horse is soft and light in the hand.

2 Educational contact

The rider takes more weight in the rein than they would ideally want, and they use that weight (through their feel) to manoeuvre the bit in the horse’s mouth to relax the jaw.

It shouldn’t be necessary to use this contact for more than two or three strides at a time, but it’s use can be repeated frequently until the horse understands the softening through the rein.It’s important to remember that the horse must be in front of the leg to justify using this aid.

3 Reward contact

After the educational contact has been used, the rider must give the hand forward to reward the horse with a softer feel. If the horse has understood the educational contact, the outline and speed of the pace will remain the same, and the horse will be in self-carriage.

Scale 4: Impulsion

It can be tricky to explain to someone, especially if they are new to riding, exactly what impulsion is. Experienced riders know what it feels like, and they certainly know what happens when their horse is lacking impulsion.

Lazy transitions, poorly balanced circles and a downhill frame are just three issues caused by a lack of impulsion. It affects jumping too; a lack of impulsion can lead to refusals, knocking fences down and even horse and/or rider falls.

“The dictionary definition of impulsion, besides meaning ‘a strong urge to do something’, is the motive or influence behind an action or process,” explains Ian.

“In riding, it’s all about energy and power, but crucially controlling that energy and power to direct it where we want is, such as a longer stride length (for example, medium or extended trot), or higher, more agile jumping.

“Impulsion means that you are riding with rhythm and purpose; your horse’s hindlegs are engaged and their back is relaxed and supple.”

Horses with a naturally uphill conformation will find it easier to move with engagement and energy, but impulsion is achievable for all horses given the right schooling and exercises.

Why impulsion matters

A horse who is active and moving with energy is more capable of being responsive to your aids. For a leisure rider, this means a more enjoyable time in the saddle, not having to continually nudge, cajole and persuade them with your legs.

I predominantly hack my horse, with some light schooling too so that he is responsive to my aids. I like him to be marching on when we’re out hacking; not like I’m having to make him take every step.

“If you’re a competitive rider, impulsion enables your horse to make transitions on exactly the stride you need, to transition up and down the gaits without losing energy and have power to burn without going too quickly,” adds Ian.

“The most important thing to remember is that impulsion is controlled energy in your horse’s movement. Don’t get it confused with speed.”

If you’re struggling to maintain impulsion throughout different gaits, or feel that a willingness to go forward with energy is missing from the partnership you have with your horse, Ian shares the following exercise to help.

“If your horse isn’t in front of the leg and working to a consistent and soft contact, it will be impossible to create or improve the impulsion they’re working with,” advises Ian.

“Impulsion is essential to create self-carriage. Without impulsion, your horse will be unable to hold their own balance, whether in an uphill frame or a lower, rounder frame.”

Exercise to improve impulsion

Ian suggests starting with direct transitions to help engage your horse’s hindlegs:

- When your horse is reacting to your leg they will increase engagement and therefore impulsion.

- In upward transitions (walk to trot and trot to canter), ensure that your horse moves quickly off your leg when asked, but isn’t running away from the leg. The contact must control the forward reaction. For example, in a walk to trot transition, your lower leg asks for the walk to step forward.

- The hindlegs should move a fraction before the front leg. This results in better engagement and creates impulsion that you can control.

- It’s the same in the downward transitions too. The front end of your horse should transition a fraction of a second before their hindlegs. This encourages them to sit underneath with their hindleg as they come forward to trot or walk.

Scale 5: Straightness

A dressage judge will spot whether a horse and rider are straight as soon as the partnership comes down the centre line towards them at the start of a test.

“A horse is straight when their body is properly aligned from poll to tail,” explains dressage rider Melissa Chapman, who runs Team Chapman Equestrian in North Yorkshire.

“When they’re on a straight line, they should be straight along the length of their body. On straight or curved lines, their hindlegs should step precisely behind the front legs. In lateral work, the horse’s hindlegs should move in the direction of movement and should not step out from under them.

“If your horse is straight you will feel an equal contact in both hands and even weight in your stirrups and seat bones. Riding movements will feel easy in both directions and your horse’s ears will be level without any tilting at their poll,” adds Melissa.

Lacking straightness

Whatever your favoured discipline, straightness is key and not having will affect your horse’s performance. In eventing, for example, a horse lacking straightness may start to struggle with technical cross-country questions or tight turns in the showjumping ring.

If asked for a sharp turn or movement on their weaker side, they could run out or refuse.

Out hacking, a horse who isn’t straight will be a tricky ride on the road, and will find it difficult to stay close to the hedge line in fields where you are trying to stay off a farmer’s growing crops.

I am from a farming family, so I know from experience how much trouble you will be in if your horse treads on precious crops.

In dressage, a horse who isn’t straight might seem stiff on one rein and hollow on the other, or they may be unwilling (or unable) to canter smaller circles on a particular rein.

They may even start using their hindquarters differently because they struggle to stay balanced over their centre of gravity and so start compensating.

“A crooked rider can also have a big impact on a horse’s balance, so it’s worth observing how the horse moves on long reins as well as under saddle,” says Melissa. “It could be that the rider needs some physiotherapy and targeted exercises as much as their horse does.”

Scale 6: Collection

Collection is the pinnacle of the dressage Scales of Training; it can only be achieved when all the other scales beneath it are in place.

The level of collection a horse has differs at different stages. For example, in a grand prix dressage test, collection is at such a high level that the horse can trot on the spot in piaffe, or turn around practically on the spot in canter pirouette.

For Pony Club and novice tests, there are movements that start to develop collection, although collection itself is not a necessity. These include when the horse comes into a halt, or changes from lengthened strides to a working trot.

As the horse stops or shortens their steps, they should step more under their body with the hindlegs and transfer a little more of their weight onto the hindquarters. This is the beginning of collection.

No matter what you’re aiming to achieve with your horse, whether that’s dressage, eventing, hacking or something else, it all starts with correct schooling, and the dressage Scales of Training are an excellent toolkit for encouraging your horse to work correctly so that they are an easier, enjoyable ride.

Main image © Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media Ltd